In May 2024, I authored an article titled "Kant and Van Til: A Response to the Reformed Classicalist." This piece addressed Matt Marino's criticisms against Van Til, suggesting that Van Til was an implicit idealist. The article garnered positive feedback from Van Tillians. While it was shared in Thomist circles, there was no notable response. However, I did receive feedback on the Van Tillian Fire blog (from hereon, VTF).

This article will provide some pushback on the comments made, but let me preface it by stating that this conversation should not be read through an antagonistic lens. A healthy and thorough discussion of this sort is severely lacking in theological circles, so I'm incredibly glad that VTF took the time to read my content and offer a thoughtful response.

Generally speaking, theology has always advanced by striving for greater clarity in the face of opposition. In this case, there is opposition both from the classical camp and from some within the Van Tillian camp. This presents us with a valuable opportunity to seek clarity together as brothers in Christ.

Articles that can be read beforehand for full context:

The context of this discussion centres on the ongoing debate between idealism and realism, and the extent to which Van Til can be categorized within either camp. Classical apologists, particularly those from a Thomistic background, often accuse Van Til of leaning toward idealism. On the other hand, VTF raises concerns that Van Til is being placed too firmly in the realist camp. I have responded to the classicalists and their idealistic accustation. This article now focuses on the "too realist" accusation.

To begin, let me quote VTF to highlight a major point of agreement.

We ought not let them [Thomists] presume the high-ground there. Often when "realists" swagger around as if they have the most common-sense view, when we pry into it, we find all manner of weirdness and counter-intuitive metaphysical baggage

Rather, we ought to start – as did Van Til – from a clear theological picture of the "self-contained" God creating all Creation in a holistic vision.

Van Til's Problematic Idealism? (Comment section)

Exactly. This is the point of the Van Tllian agreement. I echoed this as much in my article when I stated, borrowing from Van Til, that “...man exists in an 'atmosphere' of revelation”

VTF found my statement that "...man exists in an 'atmosphere' of revelation" somewhat lacking in clarity and wished for a more detailed explanation. Put simply, this means that God created both the subjects (us, as thinking beings) and the objects we encounter and experience in the world. Subjects and objects are made for each other, and both are integral parts of God's grand design for creation. Both are inescapably tied to His creative decree.

This is the same as saying, as VTF did, that we must begin with a "clear theological picture of the self-contained God creating all of creation within a holistic vision". All facts are connected to God's eternal plan—there are no "rogue molecules." God knows all things comprehensively because He governs all things completely. On this point, VTF and I agree. I will aim to expand on this further in the upcoming sections of the article and highlight specifically where and why I disagree with his formulation of Van Til's epistemology.

So, with this agreement outlined, let's consider the debate between realism and idealism.

Realism, idealism and representative realism

VTF explains that realists view perception as direct access to external objects, believing that we see and interact with the world as it is. Thomists generally support a form of naive realism, explaining it through theories of how the mind abstracts "forms" from objects or how objects imprint forms onto the mind.

In contrast, idealists argue that ideas or concepts mediate our experience of the external world, suggesting something stands between us and reality.

VTF then introduces the concept of representative or indirect realism, which maintains that real objects exist outside the mind, distinguishing themselves from metaphysical idealists (who believe that reality is fundamentally mind-generated). The indirect realist believes that a person does not have direct access to the objects in themselves, but to "representations" of those objects - which are produced by sense perceptions. Thus, we do not perceive the world itself, but an internal perceptual copy of the world generated by our conscious experience.

Representative/indirect realism

Idealism, at least in the way that Marino and other classicalists would define it in the context of their critique against Van Til, comes down to the Kantian (idealistic) distinction between the noumenal and the phenomenal. That is, the distinction between reality as it is (the thing in itself), and how we perceive it.

Epistemological idealism holds that all knowledge is based on mental structures, and not on things in themselves. In this sense, the mind moulds the facts of experience to fit a predefined conceptual framework (like water is made to fit the shape of the ice tray).

Indirect realism would not go as far as epistemological idealism, but rather claim that knowledge is based on the "representations", or the "sense-perceptions" generated by the objects being perceived. This view is historically related to empiricists like John Locke and Thomas Reid. On this account, correct perception of the world would be contingent on proper functioning cognitive faculties (which lends itself towards an externalist foundationalist theory of epistemic justification. More on this later). So, although indirect realism suggests that our perception is not identical to reality itself (since it's mediated), it doesn't necessarily claim, like Kant does, that the true nature of reality (the noumenal) is completely beyond our grasp. Instead, it implies that our perception provides us with an indirect but still meaningful representation of the external world.

Thus, in idealism, the mind plays an active role in "shaping" the facts of experience so they can be known. In realism (both forms), the mind plays a passive role. Reality "imprints" itself on the mind.

VTF correctly notes that the indirect realists, unlike typical metaphysical idealists, still hold there are real objects “outside of the mind” we are encountering as opposed to metaphysical idealists who do not believe in an independent external reality.

The Classical apologist's charge

VTF argues that the Classicalists are primarily concerned with a particular model of "knowing" (epistemology) where concepts mediate between us and our direct experience of the external world (i.e., between subjects and objects). According to them, this model introduces scepticism, effectively placing an insurmountable barrier between humanity and God, as well as His revealed truth.

The concern raised by the Classicalists is valid: both epistemological and metaphysical idealists argue that the human mind plays a "constructive" role in shaping our knowledge of reality.

The Classicalists argue that if the mind actively alters or shapes the facts of experience, we lose the ability to access objective knowledge. Instead of understanding the world as it truly is, we only perceive subjective interpretations, making it impossible to claim any knowledge that is universally true and independent of personal bias. For knowledge to be objective, the mind must reflect reality as it is, without imposing its distortions or constructions.

Classicalists detect elements of Kantian idealism in Van Til's work. Consequently, they rigorously oppose Van Tillianism because they are determined to prevent any form of idealism from infiltrating Christian theology. This stance is commendable if Van Til is indeed infected by Kant.

If the human mind takes on a constructive role in the process of knowledge, so that mental concepts act as a barrier preventing us from directly accessing external objects, we inevitably fall into what is known as the egocentric predicament. In such a scenario, the human mind becomes autonomous, leading to scepticism. It then becomes impossible to determine whether what you believe about a particular object truly represents the object itself. More crucially, if God reveals Himself through His Word, the meaning of His words would be limited by the subjective interpretations of the human mind. As a result, God, who is inherently transcendent and incomprehensible, would ultimately become entirely unknowable. This is the point of chapter 13 of Van Til's Introduction to Systematic Theology.

VTF's reply to the Classicalist

VTF argues that my portrayal of Van Til as a "theistic realist," meant to counter the classical charge of idealism, is insufficient. He contends that categorizing Van Til this way is fundamentally flawed. According to VTF, objective truth about the world is not determined by how it appears to us, but by how it appears to God. For this reason, he believes that any "realist" approach is inherently linked to a sinful desire for autonomy. Why? Because, in its traditional sense, realism assumes that subjects can know objects directly, without any external or internal "help"—a notion that VTF sees as contradictory to our dependence on God's revelation.

VTF then argues that it is more accurate to describe Van Til as an indirect realist, rather than a theistic realist or an idealist. This point is particularly intriguing because, upon closer examination of VTF's epistemology, it appears that he views Van Til as an epistemological idealist...

He writes that...

... [The] “representative realist” unlike typical metaphysical idealists, still thinks there are real objects “outside of the mind” we are encountering. This is what makes Van Til a “realist” rather than a typical “idealist” and it’s why Lane Tipton, Arne, et. al. push back when Classicalists smear Van Til with the “idealist” label.

While it's true that Van Til believed in the reality of an external world, this isn't the central issue for me or Tipton. We agree that Van Til acknowledged the existence of God, the external world, and humanity's place within it. What we challenge is the broader claim that Van Til was an idealist of any kind. On this point, it seems VTF ultimately concedes to the Classicalists, acknowledging that Van Til was "not an idealist in the sense typically criticized".

Indeed he writes that...

[Van Til’s] “idealism” is not only unproblematic for Christian theism, but rather – ironically – highly motivated by Classical theist metaphysics.

Having identified Van Til as an indirect realist, VTF seems comfortable also labelling him as an idealist, though he doesn’t see this as “problematic”. This suggests that VTF views Van Til’s epistemology as aligning with a form of idealism, but not the kind that would trouble Classicalists. While the notion of describing Van Til as both a representational realist and an idealist is complex (and might even be contradictory), let’s rather focus on how VTF clarifies his position more straightforwardly, and take it from there:

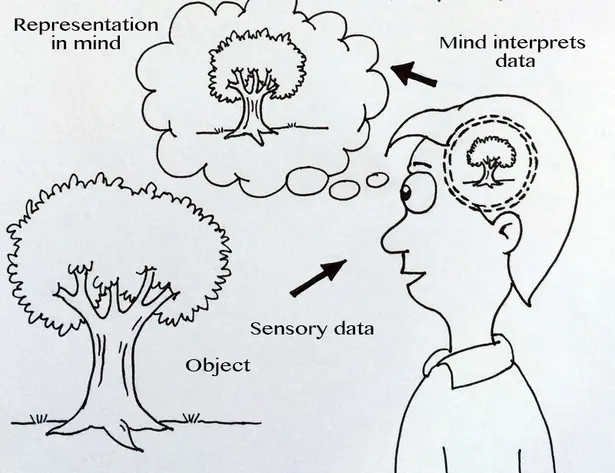

He provides the following image to explain what he means by "representative realism" or Van Til's idealism:

The preceding graphic can likely be used to portray both indirect realism and epistemological idealism. It depends on how the representation (phenomenal) of the perceived object (noumenal) is generated.

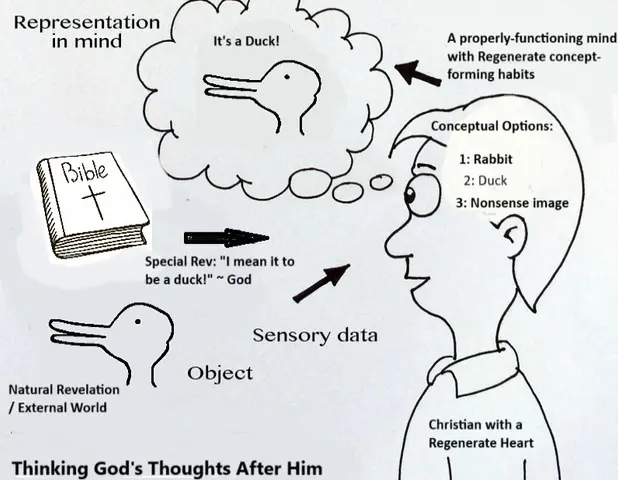

VTF then expands on this visual summary and applies it to Van Til as follows:

In this visual representation, VTF has immediately moved closer to idealism away from representational realism.

Let's unpack.

This image illustrates an idealistic perspective on how one might understand the world. A person perceives an object (a duck-like shape) from the external world. This perception involves sensory data that provides different conceptual options - such as interpreting it as a rabbit, a duck, or just a nonsense image. The Bible (representing special revelation) is presented as guiding the person towards a proper understanding. In this case, it explicitly communicates, "I mean it to be a duck!" indicating divine intention. Then, with a regenerated heart and proper conceptual habits, the person interprets the image as a duck, aligning their perception with divine revelation.

VTF's answer to the Classicalist turns out to be no answer at all, but rather a concession that they are right in their idealistic charges.

Problems with VTF's epistemology

In the VTFs example, the person (subject) is perceiving some kind of object. The subjects then form various "options" for this object could be: A duck, a rabbit, nonsense etc. In the image, the object itself is unknowable, and it is the mind that must assign meaning to it. If one person believes it to be a duck, they are equally justified as the person believing it is a rabbit or a person believing it is nonsense. No one person has any upper hand over another - it's all subjective.

VTF believes that this issue can be resolved through supernatural revelation. God declares that the object is a duck, and, as a result, the person viewing it through the lens of God's special revelation forms the belief that it is indeed a duck. But does this truly solve the problem? After all, doesn't God's revelation also come to us through our sensory data and experiences? If we know the objects in this idealistic manner, the same would apply to any words we encounter in Scripture. We are still required to interpret and filter God's words through our subjective minds, which means that the interpretation of God's Word becomes just as subjective as the interpretation of the object itself. VTF's solution, then, merely shifts the problem back one level.

I'd suggest that VTF spends some time in chapter 13 of Van Til's systematic theology. I spent some outlining and explaining this chapter in this article, but will summarise it in part here.

According to the Kantian critique, every person reading the Bible does so with their unique background, culture, and personal experiences, influencing their understanding of the text (just like it influences you with your interpretation of duck/rabbit). The way they interpret the attributes of God, such as His justice or mercy, is coloured by their personal and cultural context making God fundamentally unknowable.

This Kantian challenge thus suggests that God, being transcendent, cannot be captured by human concepts and language, even when God "tries" to reveal Himself via the Bible. When the Bible reader encounters descriptions of God's nature, they are grappling with the task of understanding a being who is fundamentally beyond full human comprehension. This raises the question of how much of God's true nature is being grasped through these descriptions (if any). The result is pure scepticism when it comes to knowing God, with the knowledge of God people think they have is pure projection on their part - forming God in their image.

Rather than addressing the Classicalists directly or offering a stronger alternative to what I initially proposed to Marino in my original article, it seems that VTF has inadvertently fallen into an idealistic mindset. Now, I don't want to suggest that VTF is, in fact, an idealist. I would argue that VTF likely holds many of the same beliefs that I do about objective knowledge, the knowledge held by unbelievers, God as the necessary foundation of intelligibility, and the indispensable role of God's Word in obtaining true knowledge. However, I believe VTF has not successfully captured the correct way to present these ideas from a Van Tillian perspective. So, allow me to offer a different approach to understanding the situation, building on my claim that Van Til was a "theistic realist."

Theistic realism

Quoting a piece from my prior article, not how Van Til differs radically in the way he approaches the traditional debate between "realism" and "idealism".

Van Til encourages us to shift our philosophical starting point.

Rather than beginning with the debate between realism and idealism (what Lane Tipton describes as the "horizontal relationship" between subjects and objects), we should consider the "vertical" relationship involving subjects, objects, and God their Creator.

This fundamental shift underpins Van Til’s approach as introduced in the opening sections of his Survey of Christian Philosophy. Here, Van Til sets his perspective apart from both classicalists (realism as traditionally understood) and Kantians (idealism as traditionally understood). He does not align strictly with either camp (although he does express a preference for the realist philosophies of ancient thinkers over modern ones, praising their pursuit of objective truth).

Van Til departs from the traditional starting points of the debate (i.e., over-reliance on the object (realism) or over-reliance on the subject (idealism)) and essentially claims that the more important question to answer at the outset is the relation between God, the subject and the object. In VTF's example, there is an over-reliance on the subject. In the classicalist camp, there is over-reliance on the object.

This different starting point for Van Til means it's difficult to construe him as either a realist or an idealist, but his system shares more in common with traditional realism than idealism - because idealism asserts the autonomy of the human mind in a very explicit fashion, whereas realism attempts to secure some kind of objectivity apart from the influence of subjects.

Here Van Til asks the question very plainly:

How can the human mind know anything about any of the facts of the universe [objects] if these facts as well as the mind itself [subjects] are not related upon the basis of a more fundamental unity in the plan of God?

Cornelius Van Til, A Survey of Christian Epistemology

Van Til posits that the unity of the subject-object (or the one and the many, or law and fact) relationship is not centred on human cognition. Instead (and this cannot be stressed enough), he emphasizes that the fundamental principle of their unity is the plan of God. This claim is directly in contradiction with idealism (and VTF's presentation of the knowing process) which asserts that the unity of the relation is grounded in human cognition.

The doctrine of creation ex nihilo establishes a world that is external and created, ensuring that subjects and objects are interrelated in a way that facilitates objective knowledge of what God has planned, created, and revealed. Contra Kant (and more akin to realistic philosophies), the human mind (subject) encounters intrinsically intelligible objects, being both created by God and revelatory of Him.

If you reject what Van Til teaches here, then you either consider the human mind as the ultimate authority in the process of knowing (the subject), or the facts of experience are seen as ultimate (the objects).

However, both these alternative positions encounter significant problems when fully developed:

Firstly, those who assume that the human mind is the ultimate authority face the challenge of proving that their reasoning accurately reflects reality. They are trapped in an egocentric predicament. There can be no external validation to confirm that the mind’s conclusions truly correspond to the world as it is. They are forever trapped in an ocean of subjectivity.

Secondly, those who believe objective reality is the ultimate authority struggle to justify how the mind can reliably comprehend or trust these facts that come to it, or how impersonal matter and abstract concepts can provide a sufficient explanation and confidence that our minds can grasp and truly understand reality as it is. If we assume the facts of the world are independent of the mind, it remains unclear how we can ensure that our understanding of them is correct.

The reason for this predicament is that neither abstract ideas nor impersonal facts can adequately explain how we can be confident that our understanding aligns with reality. This confidence is crucial at the very beginning of forming any worldview, not something that can be addressed later. Without a clear basis for this connection between the subject and the object at the outset, both approaches fail to provide a reliable foundation for knowledge.

A coherent understanding of knowledge can only rest on an absolute and personal God, one who exists before all created things, whether these are subjects or objects. Without faithfully acknowledging and growing into this foundational truth, all human attempts to make sense of the world inevitably fall short.

Let me expand on the above by drawing on Greg Bahnsen:

In his lectures on transcendental arguments, Bahnsen outlines two distinct perspectives on human knowledge: The Christian perspective, and the non-Christian perspective:

According to the Christian perspective, God created both our minds and the world we perceive. Since God is the creator of both, our conceptual framework naturally aligns with the external world. In other words, our ability to know and understand reality is inherently reliable because both our minds and the objects of knowledge are part of God's creation. This presupposition ensures that there is an automatic correspondence between our mental concepts and the things we experience

In contrast, the non-Christian perspective assumes that we cannot know anything about God, or that we can blissfully be ignorant or deny the existence of God in the knowing process. Here, we necessarily have to start with the human mind and its presumed sufficiency to understand the world. We assume that external objects exist and can be known by the mind, but there is no intrinsic connection between the mind and the objects of knowledge. Without the assumption of God as the unifying factor, both the mind and the objects of knowledge appear fragmented and disconnected. In this framework, the mind operates with a conceptual scheme, but it is not grounded in any divine order. The goal is to avoid bringing theology into philosophy, so the starting point is human cognition, and understanding is built outward from there.

The skeptic comes along and asks, ‘How do you know there is a connection between your conceptual scheme and the objects in the world?’ This worldview by definition cannot answer the skeptic because it begins with a separation between minds and the objects in the world. There’s no connecting link. And any attempt to bridge the dividing link is going to be easily criticizable by the skeptic.

If you begin with an egocentric picture don’t be surprised when you end with an egocentric predicament. If you start your philosophy with man you end up with man separated from everything in the universe. How do you know there’s any connection between your thinking and what’s outside the mind? If pushed hard enough this leads to solipsism. If you leave God out of the picture you leave man separated from everything.

Bahnsen/Butler, Transcendental Arguments, Tape 6

This theistic realist scheme can explain quite a few things that VTF's solution fails to explain:

Knowledge in infants

Knowledge in unbelievers

In my previous article, I explained that because God precedes both the subject (the knower) and the object (what is known), and because He has naturally linked them together, subjects inevitably know objects as they truly are. This means, for instance, that my infant daughter can grasp many basic truths, even though she cannot yet comprehend a single word of the Bible. She cannot articulate belief in God, yet she knows fundamental things like the love of her parents, the difference between day and night, the need for sleep, and even God Himself. She knew God as soon as she was confronted with any other kind of knowledge (in the same way that someone is confronted with "light" when they first experience "colour").

She does not need to process these facts through a complex conceptual scheme to know them. She is, by nature, directly in contact with God's world, she is a part of it and His divine orchestration of history.

Similarly, unbelievers can truly know things in practice because they are part of God's creation, and, as such, they cannot help but know the world around them. They cannot escape the fact that subjects and objects are related in God's eternal plan, and they cannot fail to know this world truly as God's world and God Himself. However, in principle, they cannot truly account for their knowledge. This is because they attempt to position themselves as autonomous knowers, treating some other fact or standard as ultimate, rather than God. By doing so, they implicitly deny any intrinsic connection between subjects and objects or, if they acknowledge such a connection, they cannot explain how they can know it. Without God as the ultimate grounding for knowledge, their understanding lacks a foundational basis.

VTF agrees that unbelievers cannot know anything in principle. It seems, however, that in his explanation of his epistemology, he has committed himself to the position that unbelievers cannot know anything in principle as well.

As a final consideration, before we move on, VTF wrote that

Van Til explicitly says that none of the objects of our experience can be known "exhaustively" .. (pg. 214 of the pdf version of IST)... this means, contra Tipton, there will always be an inherent ambiguity in the objects of our experience.

Agreed. As finite creatures, we cannot exhaustively know anything, nor can we fully comprehend how all facts are eternally related to God. Our understanding is always limited and analogical, reflecting a partial but true grasp of reality. Neither Tipton nor I would claim that the theistic realist framework requires exhaustive knowledge of anything. In fact, as someone who aligns with externalist foundationalism (in the vein of Bosserman), I explicitly acknowledge that our knowledge is always growing and deepening. This process unfolds under the guidance of the Holy Spirit, who leads us into all truth.

The theistic realist scheme allows for true yet incomprehensive knowledge. Hence, my infant daughter can know things truly albeit in an incredibly limited fashion.

The role of Special Revelation and the knowledge of God

VTF wrote that...

Arne needs to think carefully about what Van Til means by "brute fact" and also about why Special Revelation is always needed (along side natural revelation) for any knowing. His infant daughter used as an illustration here, isn't appealing to special revelation in any of her supposed knowings. Ok, so is Arne rejecting Van Til's epistemology? Better to say your infant daughter has true beliefs that are presumptively justified (by appeal to special revelation) upon analysis.

YouTube comment

The last issue I want to address is the role of Special Revelation.

In VTF's explanation of his epistemology, the Word of God is presented as clarifying the inherent ambiguity in how we understand perceived objects.

Furthermore, as mentioned earlier, VTF suggests that even my infant daughter's knowledge must be justified through Special Revelation.

Now, while I agree that Special Revelation plays an indispensable role in our epistemology, I believe we need to provide more clarity on the specific role it plays. It’s important to distinguish how Special Revelation functions in relation to natural revelation and human knowledge, especially in cases like my daughter’s—where knowledge of certain truths exists without explicit, conscious engagement with Scripture.

Consider our knowledge of a horse or a lion. Do we need to consult the Bible to know what a horse is? Can we not understand what a horse is without referencing Scripture? Or take advanced calculus, for instance—must we turn to the Bible to solve mathematical problems?

The answer is no. We can know and understand certain things 'independently" of the Bible (please allow me to explain before gasping). It seems that the Bible often expects us to grasp some natural concepts before reading it. For example, we must first understand what a lion is to later comprehend the metaphor when the Bible refers to Jesus as a "lion".

Yet, VTF's epistemology seems to suggest otherwise, at least on the surface. It appears to imply that the objects of experience are only intelligible through the lens of Special Revelation. This interpretation raises the question: does VTF's system demand that we consult the Bible for every piece of knowledge? This simply does not equate with experience.

So, what exactly is the relationship between Special Revelation and our epistemology? I argue that, although Special Revelation does not provide us with a science or mathematics textbook, it works together with Natural Revelation to form a single, unified revelation from God that should be understood holistically. While we can distinguish between these two forms of revelation in theory, they must function together in practice.

How does this work practically? Special Revelation clarifies humanity's covenantal obligations, and our place in creation, and reveals God's nature and His plan for our salvation from sin. Without this divine revelation, where God's absolute personal authority assures us that history is in His hands and that He is the Creator, we are left struggling between the extremes of idealism and realism (with all the difficulty that comes with it as discussed earlier). Special revelation places all objects of knowledge in the right light and assures us that we can know them truly, even if we cannot know them exhaustively. It gives us the metaphysical "holistic theological picture" that allows us to consider the vertical relation between God and the subject and object.

... the object of knowledge is brought into right relationship with God once more. And an aspect of this restoration is that true light is thrown upon it by the Scriptures. The Niagara Falls cannot be seen at night unless there is a powerful searchlight that throws light upon them. The point of importance to note about this matter of Scripture is that according to the Christian theistic position the Bible is an inherent part of the system of theism as a whole.

Van Til, Survey of Christian Epistemology pg. 108

Without the Scripture as the word of the self-attesting Christ we would know no fact for what it is, i.e., as set in the only framework in which it can have meaning.

Van Til, Survey of Christian Epistemology pg. 109

VTF is correct in stating that, ultimately, my infant daughter's limited understanding of the world is grounded in the authority of Scripture. However, I think he is mistaken in how he perceives the role of Scripture. My daughter begins to know God and His creation naturally, even before she is capable of comprehending Scripture. Initially, her knowledge of God is quite basic, as she encounters Him through the world around her. As she grows, her understanding of how God has orchestrated her life and the world will expand. When she eventually engages with Scripture, she will be able to praise God even more, recognizing the deeper truth behind the beauty of His creation, now understood more fully through His Word.

Bosserman once illustrated this concept with an example: My child might know that I provide food for her, but she may believe it's as simple as swiping a magic card that somehow results in people giving us food. She doesn’t fully grasp how I provide for her, but she knows that I do.

Similarly, my daughter truly knows her surroundings and has some understanding of God, but in a very naive way. Special revelation through Scripture will help her place herself in the right context, allowing her to rest in God's promises with a clearer and fuller understanding.

For unbelievers, the situation is quite similar. The key difference is that they consciously suppress the knowledge of God, which naturally confronts them both in the world around them and within their conscience. Instead of accepting this truth, they attempt to interpret their existence in ways that are ultimately self-contradictory and lead to ongoing frustration. Even if they read Scripture, they rebel against its message and turn to human-made philosophies to escape the reality that has been evident to them since birth: this is God's world, and no one can fully escape knowing that truth. In this way, they can know things in practice because it is inescapable, but they cannot know anything in principle.

Conclusion

VTF closes his article by writing that

In Christ are – quite literally – hidden all the treasures of wisdom and knowledge…

Amen.

I'm glad I was able to provide more nuance from a theistic realist perspective, and I hope that VTF engages with this for at least one more round. I find it incredibly refreshing and helpful to refine and articulate my beliefs with greater detail and precision through these discussions.

Discussion