Over the past year, I have dedicated myself to exploring the philosophical dimensions of presuppositional apologetics, primarily through an in-depth examination of Van Til’s works. This represents a refreshing shift, as I am now transitioning my focus towards applying the insights gained from the past year into crafting a coherent argument for the existence of God.

Check out the following video for a good overview of what we'll discuss in more detail in this article...

Additionally, I aim to maintain simplicity in our discussion to ensure it is accessible and engaging for a broader audience, including many of my friends.

Why do I believe in God?

In this section, I aim to reflect upon and reiterate the thoughts of Cornelius Van Til, an individual whose work I hold in great esteem. Specifically, I refer to his pamphlet titled 'Why I Believe in God'

In this pamphlet I tried to point out in simple terminology why I believe in the God of the Bible, the God of historic Reformed theology. The God I believe in is the triune God of the Bible. I believe in this God because He Himself has told me in the Bible Who He is, what I am, and what He, in Christ and by the Holy Spirit, has done for me... I was brought up on the Bible as the Word of God. Can I, now that I have been to school, still believe in the God of the Bible? Well, can I still believe in the sun that shone on me when I walked as a boy...? I could believe in nothing else if I did not, as back of everything, believe in this God. Can I see the beams underneath the floor on which I walk? I must assume or presuppose that the beams are underneath. Unless the beams were underneath, I could not walk on the floor...

Van Til, Why I Believe in God (get the book here)

In my exploration of presuppositional apologetics, I've grown to recognize the deep and inseparable link between the God we defend through apologetics and the same God we worship daily. While this observation may initially appear trivial, it holds significant truth. Before embracing the presuppositional approach, my perception of God in the context of apologetics was markedly different from my understanding of God during worship services on Sundays...

Within the realm of apologetics, God seemed to be a distant entity that required logical and reasoned arguments to prove His existence. This portrayal of God suggested a being whose existence we could never fully ascertain. Despite our best efforts, complete certainty about His presence remained just out of reach.

This view starkly contrasts the triune God I worship, as celebrated in the traditional hymns.

I need Thee every hour In joy or pain Come quickly and abide Or life is vain

I need Thee, O I need Thee Every hour I need Thee O bless me now, my Savior I come to Thee

In my journey, I have consistently acknowledged—and now understand even more profoundly—that I need God every moment of every day. I've come to realize that without Him, life lacks meaning. In Him, I find a blessed assurance through Christ, a precious gift that cannot be taken away:

Blessed assurance, Jesus is mine O what a foretaste of glory divine Heir of salvation, purchase of God Born of His Spirit, washed in His blood

Can you see the inconsistency? When delving into apologetics and discussing the existence of God, I inadvertently ceased to regard Him as the one "I need every hour." In my apologetic endeavours, I felt self-sufficient, attempting to rationalize God's existence without feeling a dependency on Him. This self-reliance in reasoning seemed to contradict my professed need for God in every aspect of life.

This contradiction was clarified for me by Van Til's teachings. The God I have been worshipping since childhood, the same God my parents introduced me to as the sustainer of my being, who intricately formed me in secrecy and knew me before my existence was acknowledged (Psalm 139), who promises never to leave me nor forsake me because His love for me is eternal, is identically the God I have the honour of defending in apologetics. It is now inconceivable to me to treat Him merely as a hypothesis subject to verification as if He were just another empirical claim.

I don’t deny that I was taught to believe in God when I was a child, but I do affirm that since I have grown up I have heard a pretty full statement of the argument against belief in God. And it is after having heard that argument that I am more than ever ready to believe in God.

Van Til, Why I Believe in God (get the book here)

The paradox was vividly illustrated for me during a Bible study when a friend prayed for God to grant me strength and insight to argue His existence in an upcoming discussion. This moment raises an intriguing question: how can we ask for divine strength to prove the likelihood of God's existence? What does this imply about the nature of our prayer?

This reflects the essence of Van Til's apologetic approach, which aligns with biblical teachings. It posits that God is not merely a fact to be reasoned with as true or false. Rather, He is the foundation that enables us to discuss facts in the first place. God is the one who imbues all creation with its essence. When we join the Christian community in acknowledging our need for God at every moment, this encompasses every aspect of our lives. God not only created us in His image but also grants us knowledge, life, and sustains us continually. To reject the very source of our life and reason, using the life and intellect He provides, is the pinnacle of irrationality. This is why the Bible states, "The fool says in his heart, 'There is no God'."

Why do I believe in God? Because He has chosen to love me. He is the prism through which all other facts are illuminated. He reveals Himself in the natural world and through Scripture, filling me with wonder that the vast, unfathomable Creator cares for me. He is the ultimate Certainty, in whose absence there is no surety.

The proof of God's existence

Having outlined my perspective on the subject of God's existence at a high level, I would like to delve into a more formal discussion of the points I've raised. When we're questioned about the evidence for God's existence, it's crucial to understand that this inquiry cannot be approached in the same manner as other factual investigations. The quest for proof of God's existence is akin to a fish questioning the presence of water.

For instance, if I were curious about whether my mother purchased cookies, I could verify this by checking for cookies in the pantry. However, the existence of God cannot be scrutinized in this manner. Assuming that all facts should be investigated uniformly is akin to falling prey to the "crackers in the pantry fallacy" (as discussed in Bahnsen versus Stein).

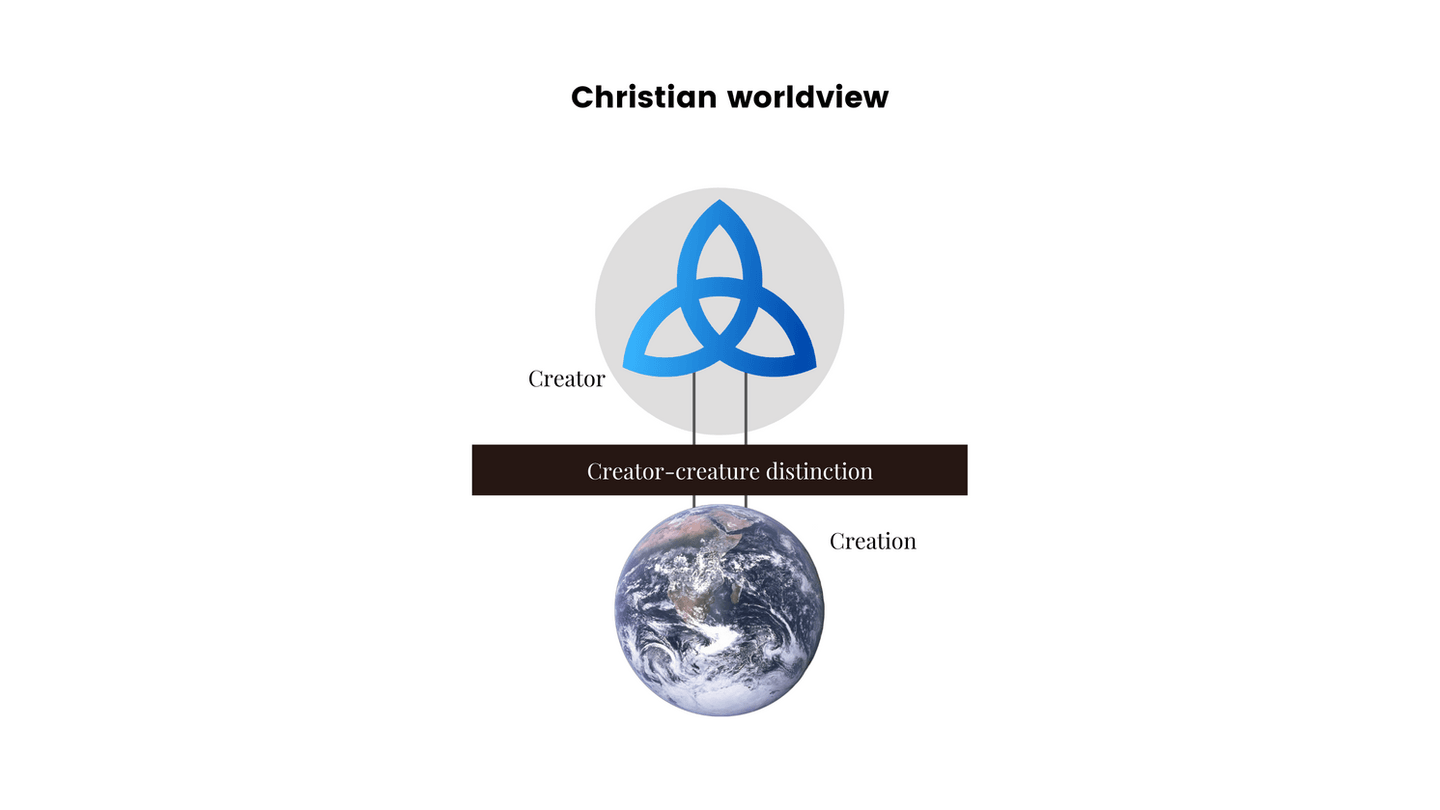

God transcends the myriad of facts within the universe; He is the Creator who assigns essence to all things. He declared, "Let there be light," understanding the nature of light even before its manifestation in space and time. We cannot discover God through laboratory experiments, nor can He be found in natural settings, the sky, outer space, or distant planets. God's existence is not contingent upon a larger framework from which He derives His identity. Should God be relegated to merely one of the universe's many facts, He would cease to be its Creator, and thus, the deity in question would no longer align with the Christian understanding of God.

Secondly, it's important to note that I do not believe it is necessary to furnish proof of God's existence in the conventional sense aimed at convincing others of His reality. Scriptural references, such as those found in the Psalms and Paul's letter to the Romans, assert that the knowledge of God's existence is inherent in everyone, leaving no one with an excuse for denial. Our goal, then, is not to convince people of God's existence but to unveil the recognition of God that already resides within them. The analogy is similar to an individual attempting to submerge a beach ball underwater; the effort isn't to convince them of the ball's presence but to assist in releasing their grip, thereby revealing what they've been actively suppressing. Similarly, our task is not to persuade others of God's existence but rather to demonstrate that they are suppressing their inherent belief in Him.

The argument for God's existence, applicable to both believers and non-believers, can be succinctly summarized as follows: The proof of God's existence is that without Him, nothing can be proven. This statement goes beyond the simple acknowledgement that our existence hinges on God; it also means that without the intrinsic knowledge of God within us, our capacity to prove anything would be nonexistent. Since God defines the essence and existence of all facts, possessing an exhaustive understanding of the world He created, denying His existence leads to a paradox where logic and meaning collapse into subjective scepticism.

Approaching the proof of God's existence mirrors the challenge of proving the existence of concepts like words or air; asking for proof inherently utilizes the very element in question. For instance, debating the existence of words employs words, just as questioning the existence of air involves the act of breathing. Therefore, a non-believer denying God's existence is akin to using language to dispute the existence of language itself.

I feel that the whole of history and civilization would be unintelligible to me if it were not for my belief in God. So true is this, that I propose to argue that unless God is back of everything, you cannot find meaning in anything. I cannot even argue for belief in Him, without already having taken Him for granted. And similarly I contend that you cannot argue against belief in Him unless you also first take Him for granted.

Van Til, Why I Believe in God (get the book here)

The reason one cannot prove anything—including the non-existence of God—without God's existence lies fundamentally in the concept that God is the precondition for intelligibility. God's revelation offers us an interpretive framework that renders knowledge attainable. To acquire knowledge, we typically rely on several key elements:

Laws of logic

Reliability of memory

Reliability of our reasoning processes

Uniformity of nature

The principle of predication (the ability to assert something about a subject)

The existence of objective morality

I will explore how the Christian worldview underpins these critical components and argue that rejecting God undermines the very foundation of our ability to know anything.

Laws of logic

From a Christian perspective, the laws of logic are not considered absolute in a manner that they exist independently, governing or constraining God. Instead, God Himself is deemed the supreme determiner of what is possible and impossible, not bound by the laws of logic.

The laws of logic, rather, are seen as a reflection of God’s inherently consistent nature. They serve as a tool through which we, in our limited capacity, can organize the facts of our experiences. This organization is done in a way that our understanding of the world mirrors, on a finite scale, God’s infinite knowledge of His creation. We employ these laws analogically to structure our knowledge systems so that they echo the divine comprehension of the universe.

Claims that the laws of logic are evidently true, on the basis of nothing but their own self-testimony, negate themselves. For, the applicability of logic to the spatio-temporal universe cannot be deduced from logical principles alone. And yet, the meaning of the law of contradiction cannot be conceptualized apart from notions of incompatibility and repulsion that are supplied by a number of contrasting principles and spheres (e.g., space, time, facts, qualities, ideas, languages, cultures, feelings, etc.). For this reason, Van Til contends that one must acknowledge the Triune God Who harmonizes universals and particulars, logic and history, subjects and objects, before he can be justified in believing that any of these pairs overlap at any point.

Bosserman, The Trinity and the Vindication of Christian Paradox (get the book here)

The laws of logic, commonly referred to as the three laws of thought, are outlined as follows:

The Law of Identity: A thing is identical to itself.

The Law of Non-Contradiction: A thing cannot be both true and not true at the same time in the same respect.

The Law of the Excluded Middle: Any statement is either true or false.

While these principles might be familiar to many, their profound characteristics include the following:

Transcendent: They apply beyond any one particular instance or situation.

Universal: They are applicable in all situations and at all times.

Unchanging: They remain constant through time.

Immaterial: They are not physical objects or dependent on physical conditions.

The Christian worldview offers a coherent explanation for these characteristics, unlike non-theistic perspectives. The very reliance on the laws of logic presupposes a worldview consistent with the nature of God—who is Himself unchanging, immaterial, universal, and transcendent. In Christianity, the laws of logic are seen as reflecting God's thinking, and humans, as God's creations, are called to emulate this aspect of His glory.

Moreover, as Bosserman points out, the laws of logic alone cannot account for their relevance to the natural world. There is no logical axiom stating that these laws must accurately describe the physical universe.

Attempts to justify the laws of logic without resorting to the divine revelation found in Scripture are ultimately untenable.

Reliability of memory and reasoning

In every investigation, discussion, or routine event, we engage with the world through our rationality and memory. As beings created by God, our ability to reason and perceive reality's consistency is best understood as stemming from divine influence, both directly and indirectly. As creatures of God, it is intrinsic to our nature to utilize our intellect to navigate and coherently make sense of the world. For Christians, this capacity is seen as a reflection of the divine, the ultimate rational Being who designed our minds to mirror His understanding and to learn about Him through both nature and Scripture.

Conversely, non-Christians who ignore the Creator-creature relationship do not recognize themselves as beings created by God. Instead, they attempt to position themselves as the ultimate authority or their own deity. This perspective traps them within their own minds (the egocentric predicament), leaving them with no assurance that their thoughts and reasoning accurately reflect the external world.

Does this imply that non-believers are incapable of rational thought? Absolutely not. Despite their rejection of a divine creator, non-believers do not embody the rebellion they profess. They remain, unknowingly, God's creations and an innate divine testimony compels them towards rational behaviour. It is through God's restraining grace that non-believers are prevented from descending into complete irrationality as they strive to distance themselves from the notion of a creator.

Uniformity of nature

The concept of uniformity in nature is intricately linked to the problem of induction, a philosophical issue primarily concerned with justifying the leap from observed phenomena to predictions about the unobserved. This dilemma was eloquently articulated by Scottish philosopher David Hume, who pointed out that all inductive reasoning, to some degree, presupposes that future events will mirror past ones without any rational basis for this assumption.

To illustrate, if I drop a ball today and it falls to the ground, what guarantees that the same action tomorrow will yield the same result? This expectation relies on a belief in nature's uniformity—an assumption that, according to non-believers, lacks a concrete justification and thus seems arbitrary. Without a solid foundation for expecting nature's consistency, the entirety of scientific inquiry stands on shaky ground.

In contrast, the Christian worldview offers a compelling explanation for nature's uniformity. According to Christian doctrine, God is unchanging and orderly, and He designed the universe to reflect His nature (as echoed in Psalm 19). God has pledged to maintain the universe in a consistent pattern, notwithstanding His ability to intervene supernaturally. Thus, natural laws are seen as manifestations of God's regular governance over the cosmos, providing a reliable framework for daily life.

This theological perspective allows Christians to navigate apparent paradoxes, such as believing both that dead people typically remain dead and yet also affirming the possibility of resurrection. This is not to say that God violates His laws but rather that He exercises His sovereignty to operate within the universe in diverse ways. Non-believers, lacking this foundational belief in a deliberate and consistent deity, often resort to attributing phenomena to chance, struggling to coherently explain uniformity or exceptions to it.

Given this background, it's unsurprising that the advent of scientific exploration primarily occurred within Christian societies, leading to the establishment of many higher education institutions under Christian auspices. Regrettably, the distancing of these institutions from their foundational beliefs has led to various contemporary challenges and inconsistencies, particularly evident in the academic sphere today.

Predication

Predication refers to the act of making an assertion or affirmation, where something is identified as the subject or predicate of a proposition, such as in the statement "the apple is red." This concept introduces us to the philosophical problem known as the "one and the many," which can be challenging to grasp. Van Til's work extensively addresses this issue, arguing that the concept of the Trinity—being simultaneously one and many—is crucial for resolving it. The interplay between unity and diversity finds its resolution within the nature of the Trinity.

The problem of the one and the many pertains to how we can make sense of the relationship between universal concepts (like "animals") and particular instances (such as "frog," which is a specific type of animal). Our ability to understand and navigate the world hinges on linking these universals and particulars. For example, when we recognize a frog as an animal, we are engaging in predication, combining the universal category of "animal" with the particular instance of "frog."

Throughout the history of philosophy, there has been an ongoing debate about whether universals (like the concept of "animal") or particulars (specific entities, such as frogs, dogs, and cats) should be considered the foundational reality. If particulars are deemed ultimate, the challenge arises in explaining how any sense of unity or commonality is achieved, given their inherent differences. Conversely, if universals are prioritized, the question then becomes how diversity and distinction among instances within a universal category (e.g., different horses within the concept of "horseness") can be explained.

Asserting that "the frog is an animal" presupposes a stable relationship between the particular (the frog) and the universal (animal). Without assuming such a fundamental interrelation, our ability to predicate, and thereby to know and understand the world, would be compromised.

Bosserman synthesizes this dilemma, linking it closely with discussions on rationality, suggesting that the coherence between the many (particulars) and the one (universals) underpins our capacity for rational thought and understanding. Without a coherent framework to reconcile the diversity and unity within our experience, the very basis of our rationality and predication would be called into question.

Although it may initially seem impractical, the “one and many” question has vast implications. The epistemological problem regarding whether our sense perceptions correspond to external reality, is ultimately one of how we may be certain that our rational categories (the one) do justice to the spatio-temporal objects (the many) they supposedly represent.

Bosserman, The Trinity and the Vindication of Christian Paradox (get the book here)

The Christian worldview addresses the problem of the one and the many through the doctrine of the Trinity, as revealed in Scripture. God is presented as a singular being who exists in three distinct, co-eternal, and co-equal persons—Father, Son, and Holy Spirit—each fully embodying the divine essence. This concept of God as both one and many simultaneously offers a unique solution to the philosophical dilemma.

Cornelius Van Til, a prominent figure in this discourse, emphasizes that in the Godhead, unity and plurality are equally fundamental. This means that the oneness of God does not overshadow His threeness, nor does the threeness compromise His oneness. This balance between unity and plurality within the very nature of God provides a foundational framework for understanding how universals and particulars can coexist coherently in the world He created.

Van Til's insight into the relationship between God's unity and plurality is crucial. It suggests that the Christian doctrine of the Trinity not only informs theological understanding but also offers a profound philosophical resolution to the problem of the one and the many. By asserting that unity and plurality are equally ultimate in God, the Christian worldview proposes a basis for coherence between the universal and the particular, thereby overcoming a longstanding issue in philosophy.

The Trinity solves the problem, not as a theoretical explanation for how universal principles and ideas control matters of fact, but as a personal Authority Who is a perfect harmony of unity and diversity in Himself, and thus uniquely qualified to guide man in developing an analogous harmony in his own life and thought. Apologetically, the Trinitarian perspective carries with it an illuminating diagnosis of sinful thinking as the self-defeating attempt to treat principles found in creation, rather than the Creator, as the ultimate sources of unity and/or diversity in reality.

Bosserman, The Trinity and the Vindication of Christian Paradox (get the book here)

For more detail on the topic, check out How the Trinity explains the problem of the one and the many.

Objective morality

The assertion that the existence of God provides the only objective basis for morality is a well-established argument. However, let's explore this idea from a slightly different angle, particularly within the context of factual investigation:

When we engage in any form of inquiry or seek answers to questions, there's an underlying expectation of honesty in reporting our findings. For instance, if posed with the question, "Does God exist?", it is anticipated that the response should be truthful and free from deceit.

This expectation aligns seamlessly with the Christian worldview, which posits God as the epitome of truth, incapable of lying. As beings created in His image, humans are called to emulate God's truthful nature. Therefore, the commitment to truthfulness in our investigations and answers is not merely a social convention or a practical necessity but a reflection of the divine character.

In a world without God, the imperative to be truthful loses its objective foundation, becoming contingent on subjective or societal preferences.

By situating the expectation of truthfulness within the framework of being image-bearers of a truthful God, the Christian worldview offers a profound justification for why honesty is not only preferable but inherently necessary in all forms of inquiry and discourse.

Closing thoughts on the proof

Cornelius Van Til articulated a fundamental principle regarding the nature of human reasoning: he argued that it should be analogical, meaning it should always acknowledge God as the ultimate reference point for all truth and knowledge. According to Van Til, human understanding is derivative, relying on God for the capacity to know anything at all. Without positioning God as the foundational starting point (i.e., not beginning with God), individuals find themselves in what's known as the egocentric predicament. This situation involves each person being trapped within their own subjective experience, which inevitably spirals into scepticism and absurdity. Interestingly, this conundrum also serves as an indirect proof of God's existence; the logical endpoint of not presupposing God is absurdity, but recognizing absurdity as a conclusion is itself nonsensical, which paradoxically underscores the necessity of God's existence for coherent reasoning.

If God is not the presupposed foundation of our understanding, knowledge itself becomes unattainable. This perspective is not merely philosophical but is echoed within Scripture, which teaches that knowledge begins with God. This underscores the profound implication that apart from God, not only does moral and ethical reasoning falter, but the very possibility of knowledge and understanding is undermined. The Christian worldview, therefore, asserts that the acknowledgement of God's primacy is essential not just for moral guidance but for the foundational basis of all knowledge and truth.

The Fear of the Lord is the beginning of knowledge

Proverbs 1:7, ESV

When the discussions are concluded, the stance of unbelievers towards their worldview can often be summarized by an inclination towards accepting absurdity over acknowledging Christ. This preference stems not from a logical conclusion but rather from a deeper, more personal resistance: an attachment to their sin. It's not uncommon to encounter atheists who vigorously assert their position of knowing "absolutely nothing," a stance that paradoxically undermines itself. This claim to know nothing, when claimed as absolute knowledge, contradicts its own premise and becomes a self-defeating argument.

The proof can thus be summarised as follows:

(1) Every inference and act of predication presupposes the existence of the absolute and personal harmony of unity and diversity, within the Triune God.

(2a) Denials that the Trinity exists are acts of predication.

[(2b) Acceptance that the Trinity exists is an act of predication.]

Therefore, (3) The Triune God exists

Bosserman, The Trinity and the Vindication of Christian Paradox (get the book here)

Ultimately, one may either accept or reject the proofs presented, but both acceptance and rejection are acts of predication that, intriguingly, presuppose the existence of the Triune God as depicted in Scripture. This situation creates a paradigm where metaphorically speaking, "heads the Christian wins, tails the unbeliever loses." Such a framework suggests that all reasoning, including the very act of deciding on the validity of proofs concerning God's existence, inherently relies on the logical and metaphysical foundations provided by the Christian worldview.

This concept underscores the inescapable presence of the triune God, who, according to Christian doctrine, sustains everything at every moment. The assertion is that God's reality is so fundamental to all aspects of existence and knowledge that even the attempt to deny Him tacitly affirms the framework He establishes. Thus, the triune God of Christianity permeates all of existence to such an extent that there is no aspect of reality, including the process of rational inquiry and judgment, where one can truly operate independently of Him.

The implication is profound: in the grand scheme of philosophical and theological debate, the acknowledgement or denial of God does not merely hinge on the evidence or arguments presented but is deeply embedded in the presuppositional foundations of how we understand reality itself. This perspective posits that to engage in any form of predication or rational discourse is to navigate within the intellectual and existential territory marked out by the Christian God, from whom there is no ultimate concealment or escape.

Where shall I go from your Spirit? Or where shall I flee from your presence? If I ascend to heaven, you are there! If I make my bed in Sheol, you are there! If I take the wings of the morning and dwell in the uttermost parts of the sea, even there your hand shall lead me, and your right hand shall hold me. If I say, “Surely the darkness shall cover me, and the light about me be night," even the darkness is not dark to you; the night is bright as the day, for darkness is as light with you.

Psalm 139:7-12, ESV

Van Til's analogy of a girl slapping her father witnessed during a train ride, poignantly illustrates the relationship between God and humanity, especially in the context of denial and disbelief. In this scenario, a girl is seated on her father's lap, from which position she slaps him. The underlying irony is that her ability to slap her father is entirely contingent upon him; without his support, sustaining her at that height, her act of defiance would not be possible.

This metaphor adeptly parallels the act of denying God's existence. Just as the girl's act of slapping her father presupposes his support, the act of denying God inherently presupposes His existence and sustenance. It highlights the paradox where the very capacity to reject or deny God is, in itself, a testament to His presence and sustaining power. The ability to question, doubt, or even reject God is facilitated by the reality of God's ongoing support of the individual's existence and faculties.

Why doesn't everyone profess belief in God?

The question of why, if the knowledge of God is inherent in all people, not everyone believes in God, is indeed compelling and invites a deeper exploration of the terms involved in this discussion.

It's important to clarify that on a fundamental level, everyone believes in God because the knowledge of God is an inescapable reality, both within us and in the world around us. This inherent knowledge, however, does not always translate into an open profession of faith. The distinction lies in the response to this knowledge; while it exists universally, some individuals choose to suppress this truth in unrighteousness, favouring the worship of creation over the Creator.

The transition from the suppression of God's truth to the profession of faith in Him is not something that can be achieved through human effort alone. According to Christian theology, it necessitates a supernatural act—the regeneration of the heart by the Holy Spirit. This process occurs as individuals encounter the Gospel of Jesus Christ, which has the power to transform hearts and minds, moving them from a state of rebellion to one of redemption.

The Bible contextualizes this transformation by teaching that, despite humanity's inherent rebelliousness (metaphorically described as "slapping God in the face" to highlight our sinfulness and defiance), Christ's sacrificial death was for our redemption. It emphasizes that Christ died for us while we were still sinners, underscoring the unmerited grace extended to humanity. This act of divine love offers a way back to God, bridging the gap created by sin and rebellion.

I wish I could spend more time on this issue, but for the sake of brevity, I urge you to please follow this link and read up more on what God did to save sinners.

Circular reasoning

The crux of the argument posits that acknowledging the existence of the triune God, as disclosed in Scripture, is a prerequisite for any discussion on the existence of God. In essence, every act of making a statement or judgment about God's existence (or the lack thereof) inherently presupposes the reality of God. This foundational perspective suggests that even the endeavor to affirm or deny God's existence is contingent upon the divine framework established by God Himself.

Having explored these premises, it naturally leads to a pivotal question regarding the basis of our understanding: How can one be certain that Scripture is indeed the Word of God? This question touches on the epistemological foundation of Christian faith and belief.

Starting from the foundational assertion that the triune God, as revealed in Scripture, is the precondition for all intelligibility, we anchor the Christian worldview. This presupposition undergirds all further knowledge and understanding. Through our discussions, it has been demonstrated that rejecting this foundational premise leads one’s worldview towards inevitable absurdity. This point should now be apparent. However, as we delve deeper, the discourse becomes increasingly intricate:

Given the myriad of worldviews available, refuting each one individually to prove Christianity’s truth is impractical, if not impossible. This approach would only yield a probabilistic conclusion rather than absolute certainty, as one cannot conclusively negate an infinite array of alternative worldviews. It is common in such debates for skeptics to rapidly shift from one worldview to another in response to the refutation of their current stance (e.g., transitioning from atheism to Islam to Buddhism, etc.), in an attempt to challenge the Christian position.

However, it's important to note that when a discussion reaches the point where the sceptic must resort to continually switching worldviews to find some theoretical alternative that could potentially rival Christianity, the debate has essentially concluded. This tactic is a clear indication that the sceptic's objections are no longer grounded in a genuine belief in an alternative worldview but are instead motivated by a desire to avoid the implications of the Christian worldview at all costs. Sye Ten Bruggencate often addresses this scenario by suggesting that debates should focus on the worldviews that the participants genuinely hold, rather than hypothetical alternatives. Arguing against Christianity by appealing to an unrelated worldview, such as Islam to defend atheism, is ultimately unproductive and reveals a reluctance to confront the foundational challenges posed by the Christian claim of a triune God as the basis for all reality and knowledge.

The scepticism that posits "some worldview out there might one day contend with the Christian worldview" holds limited practical significance yet remains a notable theoretical challenge. How, then, can we affirm that Christianity is the singular true worldview? The answer rests on the authority of the revealer—specifically, as communicated through the Bible. The Bible positions itself as the unique source of the preconditions necessary for making sense of the world, claiming exclusive capability to furnish the foundations of intelligibility. Thus, if the Bible indeed provides these preconditions as it asserts, it logically follows that Christianity, as outlined within its pages, is the sole worldview equipped to do so, based on its self-attested claims about reality.

This juncture is where we—and many presuppositionalists before us—encounter a potential pitfall: accepting God's Word as authoritative merely for its conceptual utility might lead us to adopt a conceptual framework that enables us to avoid absurdity without necessarily validating the ontological truth of Christianity. In other words, while the Bible offers a way of understanding the world that precludes irrationality, this alone doesn't automatically prove Christianity's truth in an ontological sense—that is, the actual existence of its claims beyond conceptual utility. The necessity of thinking within a Christian framework doesn't inherently affirm its objective reality (this objection is otherwise known as the Stroudian objection. Read more about it here).

The biblical narrative provides more than just a conceptual framework for humans to interpret their world; it reveals a profound ontological truth: God created both the human mind and the objects it perceives. Thus, according to Scripture, our understanding of the world inherently aligns with the reality of creation because God designed both our cognitive faculties and the external world. This divine orchestration ensures our thoughts correspond with reality, effectively addressing and overcoming the egocentric predicament. This ontological claim has epistemological consequences. If Christianity were a mere conceptual scheme used to justify beliefs, it would lose all its force.

Rather than being autonomous entities whose thoughts might randomly align with or diverge from reality, we are created in God's image, with a purpose that includes our capacity for true knowledge. This viewpoint fundamentally alters the conversation about the relationship between our minds and the world around us.

Addressing the critique of circular reasoning, particularly the claim that "The Bible is the Word of God because it says it is," it's essential to clarify the nature of the argument for Scripture's authority. Such criticisms, including those expressed by respected theologians like R.C. Sproul, suggest a misunderstanding of the presuppositional approach. The argument for the Bible's divine authority does indeed originate from the Bible itself; however, this isn't circular reasoning in the simplistic sense but rather a reflection of the coherent and self-authenticating nature of Scripture.

Van Til contends that one must acknowledge the Triune God Who harmonizes universals and particulars, logic and history, subjects and objects, before he can be justified in believing that any of these pairs overlap at any point. For the same reason, God’s Self-testimony in Scripture must be accepted on the basis of His unparalleled authority alone (Heb 6:13; Mark 1:22), since the rest of reality cannot even bear a consistent witness to itself apart from His illumination.

Bosserman, The Trinity and the Vindication of Christian Paradox (get the book here)

Remember the way God reveals Himself to us in Scripture:

For when God made a promise to Abraham, since he had no one greater by whom to swear, he swore by himself

Hebrews 6:13, ESV

God said to Moses, “I am who I am.”

Exodus 3:14, ESV

God's declaration to Moses, "I am who I am," in Exodus 3:14, encapsulates a profound truth about His nature in what might superficially appear as a circular statement. However, when God makes this declaration, it conveys the depth of His eternal, unchangeable, and self-sufficient nature. Unlike human beings, whose identity might be grounded in relationships, achievements, or attributes, God's identity is intrinsic to His very essence. He is the foundational being upon which all else depends, not defined by anything outside Himself. This self-definition reveals His uniqueness and the completeness of His existence, qualities that belong solely to the divine.

This concept of self-confirmation highlights a significant aspect of divine uniqueness. For God, stating "I am who I am" is not an evasion but a declaration of His absolute and independent reality. It's a statement that, while seemingly circular, is profoundly informative and distinct in the context of God's nature compared to any created entity.

Furthermore, the observation that all foundational reasoning involves a degree of circularity addresses an essential aspect of epistemology. The validity of human reasoning, the reliability of memory, and the laws of logic all presuppose their own integrity to be defended or proven. Yet, this circularity does not carry the same weight or fallaciousness when applied to God's revelation. The difference lies in the necessity and self-authenticating nature of God's revelation as presented in Scripture, which provides the indispensable foundation for all other forms of reasoning to be meaningful and coherent.

The revelation of God in the Bible stands as a necessary and non-fallacious circle that validates our ability to reason, understand logic, and trust our memories. This divine revelation, therefore, not only asserts itself as true but also enables and sustains the very possibility of truth and knowledge in our world.

The Holy Spirit / Christ's sheep hear His voice and the testimony of Scripture

From the outset, we've established that everyone possesses knowledge of God, as He reveals Himself both around and within us. This foundational premise sets the stage for a profound interaction with Scripture. Just as we can recognize the voice of a familiar person calling us from a distance, we innately recognize God's voice in Scripture. This recognition is not about analyzing or deducing; it's an immediate, almost instinctual understanding of divine presence and authority in the words of the Bible.

John Calvin, a pivotal figure in the Reformation, beautifully articulates this concept. He suggests that our recognition of God's voice in Scripture is as immediate and unreasoned as a baby's innate ability to distinguish between sour and sweet tastes. Just as infants do not engage in analytical thought to prefer sweetness or react to sourness, humans—according to Calvin—instinctively recognize the divine authorship and authority of Scripture. This immediate recognition is likened to hearing our Father's voice: it resonates with us on a deep, intuitive level, transcending mere intellectual acknowledgement to touch something more profound and inherent within our nature.

We receive all these books and these only as holy and canonical, for the regulating, founding, and establishing of our faith. And we believe without a doubt all things contained in them— not so much because the church receives and approves them as such but above all because the Holy Spirit testifies in our hearts that they are from God, and also because they prove themselves to be from God. For even the blind themselves are able to see that the things predicted in them do happen.

Belgic Confession, Article 5: The Authority of Scripture

Bosserman expands beautifully on the above by writing:

God’s Word in Scripture is not self-confirming in the simple sense that it is followed by the addendum “and this word is trustworthy” (although this appears on occasion—Matt 5:18; John 3:11; Rev 21:5; etc.). Instead, it is self-confirming as a light which so illuminates every other aspect of creation that they respond with their own unique testimonies to God’s nature and existence (Ps 36:9). Thus, it is better to speak of the proof for God as an instance of “spiral” reasoning, which begins with God’s self-testimony, turns in His light to evaluate other aspects of reality, and finally returns with an ever more refined and confirmed vision of God.

Bosserman, The Trinity and the Vindication of Christian Paradox (get the book here)

But we have to start with ourselves (i.e we cannot have knowledge of God from the outset)

The concept of "starting with ourselves" or what is often referred to as the "order of being" versus the "order of knowing" can indeed seem perplexing at first glance. This appendix aims to clarify these notions and address common misconceptions about the presuppositional approach to knowledge and reality.

The objection often raised is based on a misunderstanding. Critics assume that by advocating to "start with God," presuppositionalists claim to somehow transcend personal consciousness, beginning their epistemological journey from a divine or external standpoint. However, this interpretation misrepresents the intended meaning. When presuppositionalists assert that we "start with God," they are emphasizing the prioritization of divine revelation and God's reality as the primary lens through which all truths are illuminated. It's not about physically or cognitively positioning oneself outside of human limitations but about acknowledging God's ultimate authority and revelation as the foundational basis for understanding and interpreting all aspects of existence.

The critique that humans can only know in a semi-autonomous manner, with the knowledge of God supposedly following the knowledge of ourselves, overlooks a critical aspect of Christian anthropology. According to Christian doctrine, humans are created in the image of God, with the knowledge of God inherently revealed within them. This intrinsic knowledge means that the understanding of God and divine truths is not an external addition to human consciousness but a fundamental component of it.

Van Til writes:

The cosmos-consciousness, the self consciousness, and the God-consciousness would naturally be simultaneous... Man would at once with the first beginning of his mental activity see the true state of affairs as to the relation of God to the universe as something that was known to him in order afterwards to ascertain whether or not God exists. He would know that God is the Creator of the universe as soon as he knew anything about the universe itself.

Van Til, Introduction to Systematic Theology (get book here)

If we begin the course of spiral reasoning at any point in the finite universe, as we must because that is the proximate starting point of all reasoning, we can call the method of implication into the truth of God a transcendental method. That is, we must seek to determine what presuppositions are necessary to any object of knowledge in order that it may be intelligible to us. It is not as though we already know some facts and laws to begin with, irrespective of the existence of God, in order then to reason from such a beginning to further conclusions. It is certainly true that if God has any significance for any object of knowledge at all, the relation of God to that object of knowledge must be taken into consideration from the outset. It is this fact that the transcendental method seeks to recognize.

Van Til, Introduction to Systematic Theology (get book here)

Hence, we can take our proximate starting point as any fact in the universe, and we will be able to show how unless God is taken into account from the beginning (ultimate/logical starting point) there would be no knowledge at all. One of the reasons we can trust that our proximate starting point isn't blinding or ultimate is because we give weight to God's light as the most important light of all the lights we might encounter.

This should not be controversial. God does indeed reveal to us in Scripture that He reveals Himself to us, in us. The knowledge of God is inescapable.

John Calvin also makes the point near the start of his Institutes:

But, though the knowledge of God and the knowledge of ourselves be intimately connected, the proper order of instruction requires us first to treat of the former, and then to proceed to the discussion of the latter

Conclusion

Reaching the conclusion of these reflections, it's my heartfelt wish that you've gained a deeper understanding of the topics we've navigated together. Reflecting on Van Til's poignant words shared at the outset, we're reminded of the foundational role of belief in the God of the Bible in underpinning our understanding of the world. Just as one trusts in the sun that has illuminated their path since childhood, or in the unseen beams that support the floor beneath them, so too does belief in God serve as the bedrock of our reality. This analogy beautifully captures the essence of presuppositional thought: the necessity of God's existence as the foundation for all knowledge, understanding, and existence itself.

The call to recognize and not evade the reality of God is clear. There is no escaping His presence, for we are all destined to encounter Him, whether in this life or the next. The urgency of repentance and accepting Jesus Christ's sacrifice is underscored by the inevitable facing of God's justice. This message is not merely a theological assertion but a profound invitation to reflect on one's relationship with the divine, the nature of belief, and the path to reconciliation with God through Christ.

It is with a prayerful heart that I encourage you to consider these words and the deeper implications they hold for your life. The invitation to explore and embrace the truth of God's Word is open to all, with the hope that it will not be dismissed until it may be too late. May the journey through these discussions not only inform but transform, leading to a richer, fuller understanding of the profound relationship between the Creator and His creation. "I shall not convert you at the end of my argument. I think the argument is sound. I hold that belief in God is not merely as reasonable as other belief, or even a little or infinitely more probably true than other belief; I hold rather that unless you believe in God you can logically believe in nothing else. But since I believe in such a God, a God who has conditioned you as well as me, I know that you can to your own satisfaction, by the help of the biologists, the psychologists, the logicians, and the Bible critics reduce everything I have said this afternoon and evening to the circular meanderings of a hopeless authoritarian. Well, my meanderings have, to be sure, been circular; they have made everything turn on God. So now I shall leave you with Him, and with His mercy." - Van Til, Why I Believe in God

Discussion