In the interest of better understanding the Reformed Thomist movement, this article will be a study of moderate realism. Moderate realism is sometimes touted as the only philosophical view that is Biblically consistent (particularly with Romans 1). The reason for this, the argument goes, is that moderate realism is the only philosophy that secures objectivity in interpretation as opposed to idealism. Moderate realism is supposed to secure the objectivity of God's revelation in nature leaving men without excuse. In this article, we will be following Dr Thomas Howe (B.D., 1985; B.A., 1985; M.A., 1992; PhD, 1998) in his book titled Objectivity in Biblical interpretation in which he dedicated Part II of the book to outlining the moderate realist position which he the subsequently applies to Biblical interpretation. Dr Howe is a Professor of Bible and Biblical Languages at Southern Evangelical Seminary (SES).

This article is merely meant to be a study and not a critique. Moreover, I do not consider myself a Thomist or a moderate realist. This article exists for the sake of understanding and assisting in the currently raging debate on Thomism in the Reformed world by shedding light where darkness might still reign.

What is philosophical realism?

Realism, broadly speaking, is the notion that reality has a cognitive authority over the mind. Thus, reality has an existence independently of our thoughts or beliefs about it.

In terms of the problem of the one and the many, realists usually assert the actual existence of universals (e.g. dogness, redness). In contrast to this, nominalists assert that universals don't exist, but are merely functions of our language. Interestingly, links have been made between nominalism and idealism [1].

What is philosophical idealism?

Idealism on the other hand, broadly believes that reality is indistinguishable from human perceptions. Thus the question, if a tree falls in the forest and there is no one to hear it, does it make a sound? There are many flavours of idealism (e.g. Kantian idealism, Hegelian idealism, American idealism etc.) however for our purposes here, we will remain with the simplified definition above.

What is moderate realism in a nutshell?

Moderate realism finds its roots in the philosophy of Aristotle (384–322 BC). Whereas realism believes in the actual existence of universals (or forms) [2], moderate realism believes that the forms don't have a separate existence of their own outside the particulars of experience. The universals exist within the particulars, albeit in a particularised fashion. The mind then abstracts the universal from the particular, and then the universal exists in the mind of the observer. However, the mind was passive in this process so as to avoid the subjectivity that comes with idealism.

Introduction

"... the way in which a theorist addresses the questions of epistemology are ultimately based on his metaphysics. Since one’s view on the nature of meaning is a foundational element in hermeneutics, the relation of one’s view of meaning to epistemology and metaphysics indicates that, ultimately, hermeneutics itself is based on one’s view of the nature of reality." [3]. We now start our task of following Dr Howe as he introduces moderate realism. Recall that Dr Howe's book is ultimately about Biblical interpretation and hermeneutics. Dr Howe is making the important point that metaphysics (your view of reality) is tied with epistemology (how you know about this reality). For the Thomist (moderate realist), the moderate realist position is a metaphysical doctrine that has epistemological implications as we will see.

"Reality is that which exists, or, as we have phrased it, “That which is.” Essentially, the discipline of metaphysics asks the question, “What is that which is?” In Metaphysics, we are inquiring into the nature of existence." [4]

Howe then provides a certain dependency between the schools of philosophical enquiry. First is reality, "That which is". The second, dependent on the first, is metaphysics, "What is that which is?" The third is epistemology, dependent on the first and the second, "How do we know that which is?"

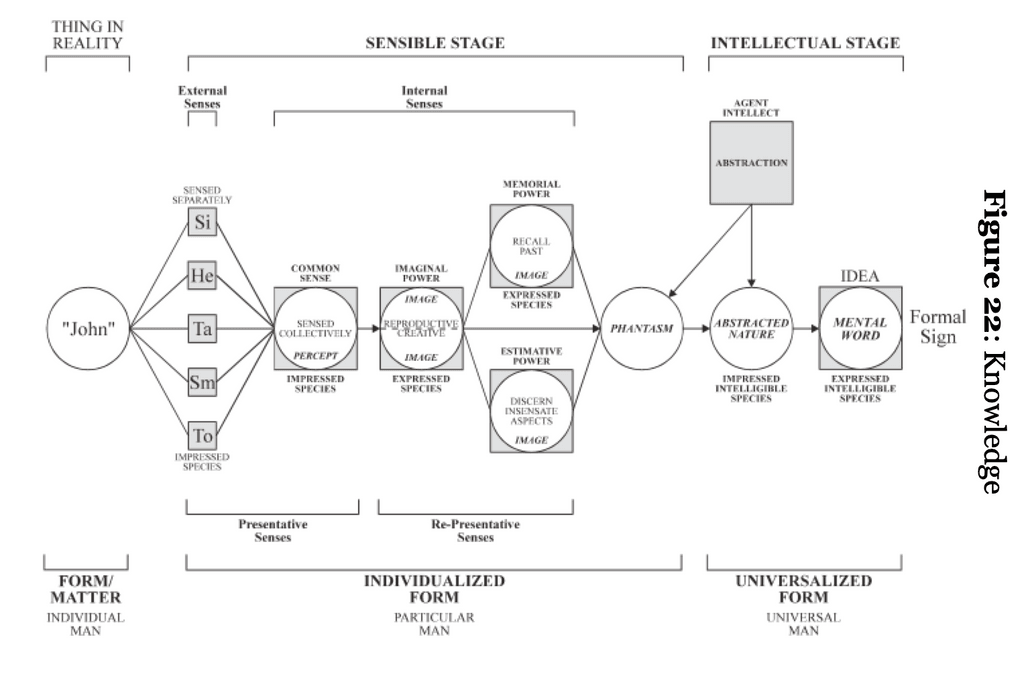

Howe then provides a helpful diagram to represent the position he will be outlining. He indicates that he will explain the moderate realist view ("What is the which is?"). The diagram he provides basically has four sections.

First, forms (universals) exist in the mind of God as ideas. In the event of Creation, God spoke and imposed Form on matter to create the thing in sensible reality (remember, the particular horse exists as a form that is particularised by matter: Hence, it is a form/matter composite). The mind of man, in knowing the created thing, abstracts the form from the sensible thing in reality. The form then exists in the mind of man. The form of the thing known is given by the thing in sensible reality and not the mind of man (hence, moderate realism is not nominalistic and idealistic). The object of knowledge is reality and not our ideas about reality. Notably, Howe does not represent the forms in the mind of man in the same way he represents them in the mind of God. This is most likely to indicate something of the Creator-creature distinction [5].

Do you enjoy our content? Please subscribe on YouTube

Our videos will provide overviews of our research and articles as they are published, including interviews with top experts in the field.

"According to the Moderate Realist view, all things exist in God’s mind before their existence in the finite world of things. God created the matter out of nothing and imposed upon it a form, thereby creating a thing in reality. This creative event is characterized in the Scripture by the phrase, “...and God said.” The resultant real object is composed of form and matter" [6].

In terms of communicating what man knows, the meaning exists as the form in the mind of man. Man then says/writes (analogous to the way God creates) and imposes meaning on matter (i.e. language) in order to create a text (either audibly or in written form) in sensible reality. The mind of the reader/hearer can then abstract the meaning from the text, such that the form exists in the mind of the reader/hearer just as it existed in the mind of the author [7]. According to Howe, God made all specific meanings possible, and some specific meanings actual (e.g. His Word), humans make some specific meanings actual. "God is not the Originator of all specific meanings." [8]

Classical foundationalism

It is indicated that the moderate realist position assumes foundationalism. That is, reality forms the foundation upon which one can base the notion of objectivity. The foundationalism assumed in the case of Dr Howe is that of Thomas Aquinas (Thomist foundationalism) expressed in the first principles of thought and being [9].

Dr Howe's foundationalism is unique because it does not believe that all truth can be deductively inferred from a certain number of foundational beliefs. Rather, in moderate realist foundationalism, truths "do not have to be inferred from or derived from a foundation in order for them to rest on that foundation. Analogously, the structure of a building is based on its foundation, but the structure is not derived from the foundation." [10]. Moderate realist foundationalism, according to Howe, "all truth is ultimately based on foundations without which they could not be true." [11].

So, what then is the relationship between truths and foundations? Howe, in quoting Aquinas writes that "... whatever things we know with scientific knowledge properly so called, we know by reducing them to first principles which are naturally present to the understanding. In this way, all scientific knowledge terminates in the sight of a thing which is present." [12] Hence, the relation between subsequent truths and foundations is not deduction, but reduction. The truth of any claim must be reducible to first principles, but not necessarily deducible from first principles. Howe then provides a lengthy example in the context of hermeneutics to illustrate this principle on pages 220 - 225 approx. A particular question that arises in my mind is how this reductionist approach is different from coherentism? The examples that Howe uses illustrates how a claim is not allowed to violate the law of non-c0ntradiction (and other foundational principles). For example, he mentions the Trinity is a concept that is in line with foundational principles. But this is not enough to provide the concept of the Trinity as true.

"The point is, a knowledge claim can be based on a foundation without being derived, inferred, or deduced from it. But, nevertheless, a truth claim can be subjected to resolution by reducing it to first principles... The point is that by the reduction of claims to first truths, we have a means of testing conclusions that is [sic] grounded in objective principles. The law of contradiction, or non-contradiction, is not a subjectively determined principle, nor is it relative to a particular worldview. It transcends all world views and is the same for all perspectives. It would seem to be the case, then, that there is indeed a possibility of objectivity in interpretation because there are in fact some presuppositions that transcend all perspectives, i.e., first truths, and that by reducing conclusions to these first truths, it is possible to adjudicate between opposing interpretations." [13]

Perhaps it's not so much a matter that the reducibility of a concept makes it true, but rather that some concepts of truth claims can be resolved (outright rejected) simply because it is not in accord with these foundational principles. These foundational principles or presuppositions that transcend all perspectives must be satisfied for any subsequent truth claim to stand.

"Ultimately all truth, including true interpretations, are based upon these first principles. But, first principles are themselves grounded upon the nature of reality." [14]

Substance

A substance is a thing or nature whose property is to exist by itself and not in another thing. This definition simply asserts that substances have a reality that exists independently of anyone's perception (contra idealism). The term "substance" can be used with reference to spiritual entities as well as physical entities in as much as each entity exists as an independent being. To speak of substance is to make reference to what something is as an essence. The substance of man is his man-ness.

Substances are things that exist in extra-mental reality. Howe believes that an extra-mental reality is immediately obvious and self-evident. "Extra-mental reality appears to be self-evidently experienced on a daily basis by all who are alive. What is to be demonstrated, therefore, is not whether there is an extra-mental reality, but that this reality exists outside the mind as what is called substance." [15] Every day we are bombarded with perceptions of things that are clearly outside our control - this is the extra-mental reality. The question now is if this extra-mental reality actually exists.

Now, anything that exists must exist either in itself or in another. For example, a man exists as a being, but a sun tan can only exist in dependence on a man. Therefore, a man is a substance, but the sun tan is an accident. Therefore, every being is either a substance or an accident. "But every being cannot be an accident, for an accident cannot exist independently; else it would not be an accident, but a substance. Neither can accidents exist dependently upon prior accidents in an infinite regress, for an infinite regress is impossible." [16] This should be sufficient to prove the existence of an independent reality.

Substance and change

"In the midst of change, something must remain unchanged. Indeed, the very notion of change includes the idea that something changes. Yet, that which changes is the same thing through the change." [17] The argument made is that change is simply the modification of a substance in terms of its accidents. For example, a man can lose his tan. A tan is not essential to the nature/essence of a man, hence it is accidental.

Substance and predication

Predication (as we've stated in previous articles on this website), is simply the attribution of a property to a subject. For example, "The man is tall", predicates the property of "tallness" to the subject "man".

Interestingly, accidents cannot be predicated on accidents unless both are accidents of the same substance. Notice in our example above that "man" is the substance, and "tall" is the accident. If there is no substance, then predication cannot make an assertion about the essence of anything. "Without substance, there is no reason to assert that a thing is white as opposed to non-white because there is nothing about which to make any assertion. Without substance, which is the essence of what something is, there is no reason not to assert that a thing is both white and non-white. Without substance, there is no means by which to limit the number of predications, and discourse becomes meaningless." [18]

The nature of a substance (the form-matter scheme)

A substance is a form-matter composite. We introduced the concept of form earlier, but we'll reintroduce it here together with the idea of matter.

Stated simply, the way a dog differs from a cat is different from the way one dog differs from another dog. A cat and dog differ in form, and two particular dogs differ in matter. "The form makes a thing the kind of thing that it is, and the matter makes it the individual that it is." [19].

Furthermore, form can be differentiated into substantial form, and accidental form (as we have substance and accidents as discussed, both of which have being).

The form of a dog is its "dog-ness". The form is not the shape. The form, rather, determines the nature/essence of a thing. Matter (prime matter), is the common ground for substantial change. Prime matter is pure potential, void of any form. Hence, a substance is a form-matter composite where the form provides the essence, and the matter provides the individuation that makes one dog differ from another.

"Things, in reality, can differ according to what they are‒a dog or a cat‒and they can differ according to the fact that they are‒this dog or that dog. The constituent principles of finite substance, therefore, are form and matter." [20]

The knowability of a substance

The problem with the knowability of a substance is that in order to know something as it is in itself, the object known must somehow enter into the mind of the knower - otherwise, all that will be known as a mere representation of the thing known, and we're back to subjectivity where the mind is somewhat constructive of what is known (idealism). Because, if it is merely a representation of the object known then we will never be able to discover whether the representation itself actually represents the real object.

Therefore, in the moderate realist scheme, knowledge involves the presence of the real object in the mind of the knower [21].

Sense cognition

The first step in knowing is sensation. Firstly, because we require the real presence of the object in the mind of the knower, knowledge can only be possible if the object is known and the subject (doing the knowing) has something in common. The mind is immaterial [22], therefore, for an object to enter the mind we need a certain aspect of immateriality from the object. This, intuitively, is the form of the object and not its matter (see the concepts of form and matter explained above). A being is defined by its form. The form is the "whatness" of a substance. Hence, when a form enters the mind of the knower, it is the form of the thing as it exists in reality that is known [23].

A. The external senses

The five senses are known to all.

Vision

Hearing

Smell

Taste

Body sense (touch)

The point to consider here is whether the mind forms the impression of what is perceived (the object) by means of some subjective modification (i.e. idealism), or whether the senses attain the objectively real.

According to moderate realism, the sense is a passive power. That is, it does not generate the forms of cognition. The form of the real object is impressed on the senses, just like a signet-ring impresses itself on a wax. The impressed form is not generated by the wax, but the signet-ring generates the form. So the form is left impressed on the senses, and not the matter.

This immaterial existence of the form of the object that exists in reality that now exists in the mind is called the "intentional existence". Now, as the form of "dog" is impressed on the sense of sight, the sense of sight does not become another dog. It is at this point that Thomas Aquinas introduces the concept of "species".

"Species" serves to distinguish between the form as it informs matter (substance) and the same form as it informs the knower (species).

"The species is not another object, nor is it merely a copy of the object in reality. The species is the sensible and intelligible aspect, namely the form, of the object in reality as it is in its immaterial mode of existence in the knower. But, as Etienne Gilson insists, “it is of capital importance to grasp that the species is not one thing and the object another; the species is the object itself ‘per modum speciei,’ that is to say, the object considered in its action and its efficacy exercised upon a subject.”" [24]

B. The internal senses

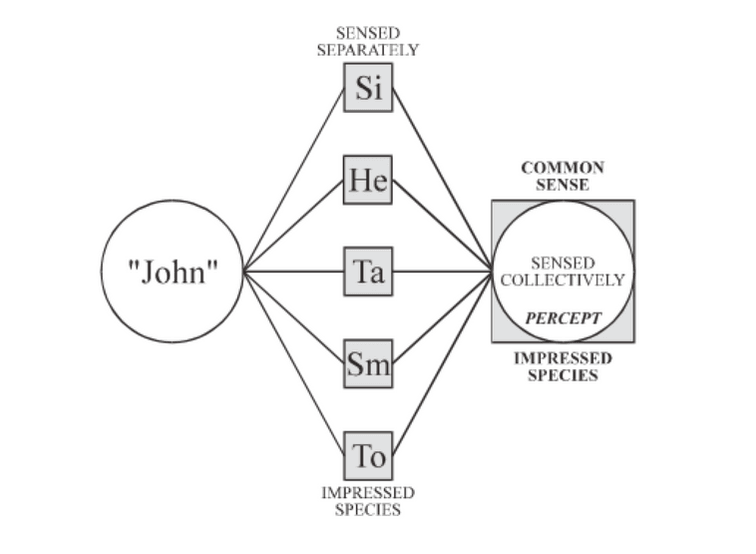

B1. The common sense

Sight can distinguish between red and blue, but not between red and warm. There must, therefore, be a unifying power by which the mind is able to unite all of the sensible aspects (sight, smell, touch etc.) into a single unifying perception. This power is called "common sense". Common sense is that “to which all sense-perceptions must be submitted, as to their common centre, to enable it to judge of them and to distinguish between them.” [25].

Howe provides the following diagram to explain the preceding:

B2. Imagination

Common sense only functions when the object is actually being perceived. However, we can recall some experiences we have had in the past. Even though the object might not be present anymore, we can recall the sensible species which was originally the result of the previous sense experience.

"The power of the imagination is composed of two aspects, the reproductive and the creative. The reproductive imagination is that aspect by which the mind is able to represent (re-present, or present again) things in the mind. The creative imagination is that aspect by which the mind is able to combine the re-presentations or portions of re-presentations into images which have never actually been the objects of the senses" [26].

As we have already discussed, the real object enters the mind by means of its form. From the form, the mind is able to generate an expressed species (as a follow-up step after the stage of the impressed species). The expressed species is called a "phantasm", which means "image". Now, this expressed species does not succumb to the idealist gap, as the real object is also present in the mind by virtue of its "intentional existence". A comparison can be made thus between the real object and the expressed species to ensure that the expressed corresponds to reality [27].

Intellectual cognition

The termination of the sense cognition is the phantasm by which the particular thing in reality is known as particular. The form of the thing in reality (the universal) has been received into the mind of the knower apart from the matter, but together with all the concrete conditions of matter: I.e. by the senses the mind knows the qualities of the particular thing here and now. That is to say, the mind knows the particular dog here and now as it is perceived. This phantasm, however, is not intelligible. The intelligible is nothing less than form entirely free from matter and material conditions [28].

However, experience teaches us that we not only know the particular, but also the universal. Language, for example, depends on words that have a general reference (e.g. "dog", "cat", "tree", "cow". Neither of these words refer to a particular cow).

"The process by which the mind comes to know the common nature [of the phantasm], which is in the phantasm that has been produced by the imagination, involves two powers of the soul: “By one power [the soul] makes things actually intelligible, by abstracting their forms from individual matter, and thus rendering them intelligible forms. This power is called the active [or agent] intellect. The other power is the ability to receive these actually intelli[gible] species, and so to know the objects of which they are the forms. This [is] generally called the possible intellect, sometimes . . . the passive intellect.” [29]"

A. The agent intellect

The intellect that lays hold upon the "whatness" of things as the universals is called the agent intellect. This happens by an act of illumination and abstraction in which common sense is illumined and separated from the individuating conditions (i.e. matter).

A1. Illumination

Illumination implies an act of making “visible” that which is already present in the thing, not adding something to the thing. This differentiates the realist from the nominalist.

"The nominalist claims that only particulars exist, not universals. Extreme Nominalism, according to the Moderate Realist evaluation, claims that there are no grounds for the universal in extra-mental reality. However, the Moderate Realist position asserts that the common nature or essence is present in each individual, and, rather than imposing upon the individual an aspect of commonality generated by the mind and represented by general terms, as the nominalist claims, the agent intellect simply illumines the essence of the thing and abstracts from the phantasm the common nature that is already and always present in the individual [30]".

A2. Abstraction

Abstraction is the act of the agent intellect in which it separates the common nature that has been illumined in order to form the impressed intelligible species. All the accidental features which are not necessary to the constitution of the individual as this or that kind of substance are stripped away [31] and only the essence remains (that is the essential form). The agent intellect abstracts the essence from all the other qualities like weight, colour, hair length, etc. which does not make the thing to be what it is.

This then forms the impressed intelligible species. "The impressed intelligible species which has been produced by abstraction is none other than the common nature or essence of the thing in reality. But, the notion of common nature must not be confused with the notion of the universal. [31]"

B. The possible intellect

"The possible intellect is the passive power that is actualized by the impression of the intelligible species, the latter being produced by the agent or active intellect. This intelligible species is the common nature or essence of the thing in reality that has been abstracted from the phantasm. [32]".

The passive intellect after being actualized by the impression of the intelligible species, forms a species of its own: the idea of the concept.

B1. Idea / concept

The idea is not the object of knowledge, but the means by which the thing is known.

"The idea which is formed by the action of the agent intellect is none other than the form of the thing in reality “considered as having an existence apart from the [thing itself].” [33]"

The problem of induction

Howe includes a section on Hume's problem of induction which we'll also explicate here. This is interesting for our purposes, as we've recently written an article on the problem as well.

Induction is reasoning that proceeds from particular instances of observation to true conclusions about all instances of some kind (including, therefore, unseen instances).

According to Howe, Hume's problem of induction arises because of a reliance on Empiricism and the tendency of Empiricists to be nominalists.

However, Howe is not a nominalist and quotes the following solution:

"For if each individual is so wholly distinct and different from every other as to have nothing in common with any other, then clearly one will have no reason whatever to suppose that what is true of one will be true of another; and naturally, on such a basis any inference from “some” to “all” would be a blatant non sequitur. On the other hand, if there are real natures and essences present in individuals, such that whatever pertains to the nature of one will necessarily pertain to any other of a like nature or essence, then the inference from “some” to “all” will no longer give the appearance of being so utterly unwarranted. We might even say that on this basis inductive inference really ceases to be a passage from “some” to “all” in the nominalistic sense altogether; rather it is an inference from observed cases to a nature or essence, i.e., to the actual “what” or “why” that is present in these particular instances and that determines them to be as they are. And clearly, once one recognizes something as pertaining to the nature or essence of the individuals observed, one thereby recognizes that the same thing will pertain to all other individuals of a like nature or essence." [34]

"And so the problem of induction is only a problem for the nominalist. If in fact there are natures, and if it is possible for the mind to abstract from the particular that which constitutes the nature of any thing, then any being in the past, present, or future having the same nature will be subject to the predictions of induction concerning that nature" [35].

References

[1] SpringerLink. 2022. Nominalism and Idealism | SpringerLink. [ONLINE] Available at: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10516-011-9150-3. [Accessed 23 June 2022].

[2] Plato believed in the realm of forms where they exist entirely apart from their particular instantiations of them - for example, horseness exists in the real of forms quite independently of the particular horses we might encounter on Earth.

[3] Howe, Thomas. Objectivity in Biblical Interpretation (p. 211). Thomas A. Howe, PhD. Kindle Edition.

[4] Ibid. p. 211

[5] Ibid. p. 214

[6] Ibid. p. 214

[7] Ibid. p. 214

[8] Ibid. p. 214

[9] Ibid. p. 216

[10] Ibid. p. 218

[11] Ibid. p. 219

[12] Ibid. p. 219

[13] Ibid. p. 225 -226

[14] Ibid. p. 226

[15] Ibid. p. 228

[16] Ibid. p. 229

[17] Ibid. p. 231

[18] Ibid. p. 233

[19] Ibid. p. 234

[20] Ibid. p. 236

[21] Ibid. p. 239

[22] Ibid. p. 239

[23] Ibid. p. 239

[24] Ibid. p. 243

[25] Ibid. p. 245

[26] Ibid. p.246

[27] Ibid. p.247

[28] Ibid. p.249

[29] Ibid. p.251

[30] Ibid. p.252

[31] Ibid. p.253

[32] Ibid. p.254

[33] Ibid. p.256

[34] Ibid. p.259

[35] Ibid. p.259 - p.260

Discussion