Note: A Canvas is just an informal place where I work out issues in a structured way.

The recent theological engagement between Reformed Classicalists (represented by Keith Mathison) and Presuppositionalists (as represented by the Reformed Forum and current systematic treatments of apologetics) has generated significant heat. To the casual observer, this may appear to be merely a semantic dispute among Reformed Christians—a civil war over hair-splitting terminology. Both sides, after all, stand in the Reformed tradition, affirming the Trinity, the sovereignty of God, and the folly of secularism.

To clear the air, we must first establish the substantial common ground between the two parties before isolating the core mechanism of the disagreement.

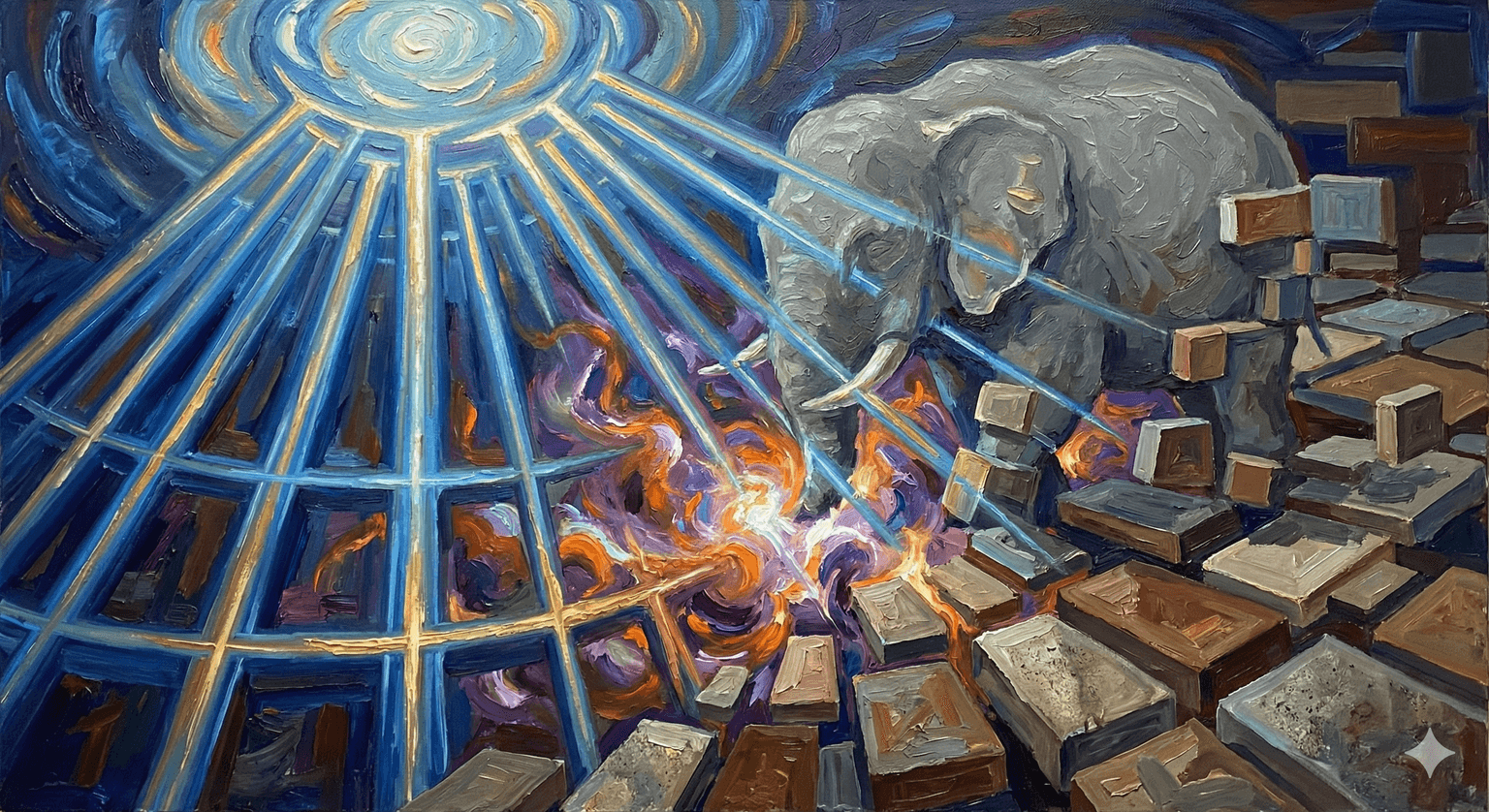

We will explore this by examining two illustrations that sit at the radioactive core of the issue: The Elephant and The Beams.

Glossary of Key Terms

Because this debate relies heavily on precise philosophical and theological distinctions, it is essential to define our terms upfront. These definitions will serve as the map for the territory ahead.

Ontology (The Order of Being): The study of reality or existence. It asks, "What actually exists?" (e.g., God, atoms, elephants). In a Christian ontology, everything that exists is either God (the Creator) or Creation.

Epistemology (The Order of Knowing): The study of knowledge. It asks, "How do we know what exists?" (e.g., sense perception, logic, revelation). The central friction in this debate is whether our epistemology (how we reason) must match our ontology (God's sovereignty) at every step.

Realism: In this context, the philosophical conviction that objects exist independently of the human mind and that the human mind is capable of contacting and knowing the "essence" of these objects directly via natural faculties. The "Realist" side of this debate (represented by theologians like Mathison) argues that the mind can know the nature of a thing (e.g., an elephant) truly without necessarily knowing its ultimate context (God).

Idealism: A philosophical system (specifically British Absolute Idealism) arguing that reality is a mental construct or a unified system of ideas. A key tenet is the "Doctrine of Internal Relations," which posits that to truly know any one part of reality, one must know its relation to the whole system. Realists accuse Presuppositionalists of being "Idealists" because they insist that facts cannot be truly known apart from God (the Whole).

Presuppositionalism: An apologetic method which asserts that the Triune God and His revelation are the necessary starting points (presuppositions) for all intelligible human knowledge. It argues that no fact can be interpreted neutrally; one must presuppose God to make sense of reasoning, logic, or science.

Van Tillianism: The specific school of presuppositional apologetics developed by Cornelius Van Til. It is characterized by the Creator-creature distinction, the rejection of "brute facts," and the belief that the antithesis between believer and unbeliever is absolute in principle but qualified in practice by common grace.

Thomism: The philosophical and theological system derived from Thomas Aquinas. In this debate, it represents the "Classical" or "Realist" position. It is characterized by the distinction between "Nature" (accessible to natural reason) and "Grace" (accessible only by revelation), arguing that reason can independently demonstrate the existence of God (Natural Theology) before Scripture is introduced.

Creator-Creature Distinction: The absolute, unbridgeable gap between the nature of God and the nature of everything else. God is infinite, eternal, and self-existent (ASEITY); creation is finite, temporal, and dependent. There is no "scale of being" that God and man share; God is "Wholly Other."

Necessary Being: A being that must exist and cannot not exist. God is the only Necessary Being; His non-existence is impossible because He is Existence itself (I AM THAT I AM).

Contingency: The state of relying on something else for existence. Everything in the universe is contingent—it did not have to exist, and it relies on God to sustain it moment-by-moment. If God withdrew His power, contingent things would vanish.

Brute Fact: A philosophical concept of a fact that is "just there"—uncreated, uninterpreted, and having no ultimate explanation. A brute fact exists without relation to a Mind that gives it meaning. The Presuppositionalist argues that if you subtract God from a fact, you are left with a brute fact (which is impossible).

Autonomy: Literally "self-law" (auto-nomos). In this context, it refers to the idea that the human mind possesses the right or ability to judge truth and reality independently of God's revelation.

Neutrality: The hypothetical "demilitarized zone" where a fact (like an elephant or a logical law) is assumed to be intelligible to both the Christian and the non-Christian without reference to their opposing worldviews.

What Everyone Agrees On

Before analyzing the divergence, it is crucial to outline the robust agreements that unite the Reformed Thomistic (Realist) and Presuppositional (Van Tillian) positions. Both sides want to be fiercely orthodox and Reformed.

Ontological Dependence: Both agree that reality is entirely dependent on God. There is no "independent" nature. God is the Creator and Sustainer of every atom in the universe. Neither want to affirm uncreated or "brute" facts.

Objective Truth: Both agree that there is an objective, rational argument for Christianity. The faith is not a leap in the dark; it is the truth about reality. Neither side advocates for fideism (blind faith).

Unbelievers Know Truth: Both agree that unbelievers can and do know things about the world (mathematics, history, science) and that they are not intellectually incapacitated in these areas because they are not Christians.

Reformed Orthodoxy: Both want to stand firmly on the tenets of Reformed theology—Total Depravity, Unconditional Election, and the authority of Scripture.

Initial Challenges

Despite the above agreements, the disagreements expose a fundamental rift in both Ontology (the nature of reality) and Epistemology (how we know it).

The Presuppositionalist argues that the Thomist, by allowing facts to be "neutral" or intelligible apart from God, implicitly accepts an ontology of "brute facts"—facts that possess a measure of autonomy—thereby compromising the absolute Creator-creature distinction at the level of being itself.

Conversely, the Thomist argues that the Presuppositionalist confuses the Order of Being (Ontology) with the Order of Knowing (Epistemology). By insisting that one cannot know a finite fact (like an elephant) without first acknowledging its infinite source (God), the Thomist claims the Presuppositionalist adopts an Idealist definition of knowledge—one that effectively requires omniscience to know anything at all, thus rendering the objective world inaccessible to human reason.

The Elephant in the Room: The Metaphysics of Meaning

Let us begin with our first analogy. Imagine a Christian and a Darwinian naturalist standing in a zoo, observing an African Elephant.

The critical question is this: Do they “know” the same thing?

The "Common Sense" Answer (Realism/Thomism/Mathison)

The "Common Sense" Answer (Realism/Thomism/Mathison) The answer, from a Thomistic Realist perspective, is an emphatic "Yes." Both observers know a large, grey mammal with a trunk and tusks, and they both grasp the essence of "elephantness" through their shared rational faculty. This agreement constitutes a neutral common ground where believers and unbelievers can stand together to debate the "ultimate truth" of the elephant’s origin.

The Presuppositional Answer

The answer is a qualified “No.” While the non-believer and the Christian are confronted by the same created reality (proximate starting point), the non-believer suppresses the truth known by the sensus divinitatis and interprets God’s world through an autonomous, anti-theistic worldview (ultimate starting point). The Christian, conversely, interprets the world in submission to God's self-revelation.

Stated simply

Thomist: "Look at the elephant's complexity; surely you see it demands a Designer?"

Presuppositionalist: "You identify the elephant as a 'mammal.' On what basis do you trust your classification categories in a chance-driven universe?"

The Illusion of Proximate Agreement

The error of the Realist position, according to the Presuppositionalist, lies in the assumption that one can strip the "creatureliness" from the elephant and still have an elephant. This is the danger of conflating Proximate Starting Points with Ultimate Starting Points.

Proximately, it is true that the Christian and the naturalist agree on the sensation of grey skin and the physics of mass, and they even use the exact same terms to describe its biology (e.g., "Loxodonta africana").

Ultimately, however, the Christian sees a Creature. The naturalist sees a Brute Fact.

If the universe is personal (created by the Triune God for His glory) then every atom of that elephant is stamped with the divine ownership. Its very definition is "a glory-reflector of God." I.e., The Christian looks and sees a Glory-Reflector. The naturalist looks and sees a Cosmic Accident.

The naturalist is not merely "missing a label" on the elephant; he is engaging in active suppression (Romans 1:18). He is observing a poem where the Author's voice rings out (Psalm 19:1–2), yet he insists on calling it random ink spills (Romans 1:21, 25). God's revelation presses upon him, but he holds it down in unrighteousness. To grant that the naturalist truly "knows" the elephant without acknowledging its Creator is to concede that the elephant has an autonomous existence apart from God (Colossians 1:17, Hebrews 1:3).

The confusion of Proximate agreement and Ultimate agreement is fatal to the Christian worldview for two critical reasons:

An elephant is not merely a biological machine but it is a derivative creature. Its very existence is sustained moment-by-moment by the word of God (Hebrews 1:3). To define it without God is to misdefine it entirely (we’ll expand on this in a later section titled “The Failure of the Artifact Analogy”).

The Thomist argues that we can know the "essence" of the elephant fully without knowing its "origin" (God). But if a fact can be fully known without God, then that fact is unmoored, drifting in a epistemological sea of Chance. It implies that the elephant possesses a layer of meaning that is independent of its Creator.

The Thomist Rejoinder: Essence, Origin, and the Rejection of Idealism

The Thomist would make a vigorous defense, arguing that this Presuppositional critique relies on a category error that confuses Ontology (reality) with Epistemology (knowledge) and reeks of Idealism.

Response to "Definition by Origin"

The Realist argues that we must distinguish between what a thing is (its Essence) and where it comes from (its Origin).

The Artifact Analogy

If you find a watch on the beach, you can truly know its mechanisms, materials, and how to tell time with it, even if you are ignorant of the watchmaker. Your knowledge of the watch is true (it corresponds to the object) even if it is incomplete (it misses the source). Similarly, the Darwinian naturalist and Christian can look at the same African Elephant in the zoo and know it truly without knowing where it came from.

To say the atheist misdefines it is to adopt a definition of knowledge that requires omniscience (knowing all relations) rather than human knowledge (knowing the nature of the object). This leads to the charge of idealism:

The Charge of Idealism (The "Infection" of Van Til)

The Thomist argues that the Presuppositional demand (that a fact is unknowable apart from God) is not derived from Scripture, but from a specific philosophical school that "infected" Van Til's thinking: British Absolute Idealism.

The Hegelian Root

This British Idealist school of thought traces its lineage back to G.W.F. Hegel, the German philosopher who famously declared, "The Truth is the Whole" (Das Wahre ist das Ganze). Hegel argued that finite things (like a flower or a man) have no independent reality but they are merely "moments" or transitioning aspects of the one Absolute Spirit. He famously saw the historical manifestation of this Absolute Spirit in concrete events, such as when he watched Napoleon ride through Jena after his victory in 1806, describing the Emperor as "the world-soul on horseback."

The Doctrine of Internal Relations

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, British disciples of Hegel (such as F.H. Bradley and Bernard Bosanquet) formalized this into the "Doctrine of Internal Relations."

The Doctrine: This posits that relations are intrinsic to the nature of a thing. You cannot define object "A" in isolation; "A" is defined entirely by its relationship to "B," "C," and ultimately, the entire system of reality (the "Absolute").

The Destruction of Essence: The Realist points out the fatal feature in this system: if a thing is defined wholly by its relations to everything else, it has no "hard core" of being in itself. It has no independent essence. As such, to know anything at all, you have to know everything as some unknown relation can upset what you think you know.

If the elephant is just "that which is related to the jungle, the sun, the atoms, and finally, the Absolute," then the elephant itself evaporates. It becomes nothing more than a knot in a web, with no substance of its own.

This logic inevitably leads to Monism (everything is one). If the "part" (i.e. the elephant) is nothing without the "whole," then individual things are just illusions; only the Whole exists.

The Thomistic fear is that Van Til, by insisting that the elephant cannot be known apart from God, has structurally adopted Hegel’s view. They argue this turns the Creator-Creature distinction into a Whole-Part relationship, dangerously flirting with Pantheism where the world dissolves into God.

Mathison’s Critique

Keith Mathison argues that Cornelius Van Til, during his doctoral studies, unconsciously absorbed this Idealist logic and baptized it into Reformed theology. He writes, “As a child, he [Van Til] was raised a Christian. He was catechized in the Reformed faith. Then in school, when he is older, he finds himself sitting under teachers who adhered to idealist philosophy. He becomes fascinated with idealist philosophy and wants to communicate with those who adhere to idealist philosophy. From a very young (and impressionable) age, he is constantly reading the works of the idealists. Idealism is regularly the topic of his writing. Throughout his earliest years in the academic world, he is immersed in idealism. To switch metaphors, it becomes part of the very air he breathes… It is not terribly difficult to imagine how this young Reformed Christian might have thought during these formative years. He is constantly seeing these idealists claim that in order to know anything truly, one must know all things truly. He repeatedly sees their claim that omniscience is necessary. It’s not difficult to imagine him thinking: ‘They are correct to reject atomistic epistemology and say that in order to know anything, one must know all things, but that puts them in an impossible situation because man can’t be omniscient. It’s too bad they reject the Triune God because then they’d have a solution to this epistemological problem. If we just replaced the Absolute with the Triune God, we’d have something.’ Now, I don’t have any documents proving that this was his process of thought in those years. It is speculation, but it is speculation based on many things he said in his writings repeatedly over the decades of his life. ” [Mathison, A Response to the Reformed Forum on Cornelius Van Til: Part Two]

Van Til asserts: “I know a fact truly to the extent that I understand the relation such a fact sustains to the plan of God.” (Survey of Christian Epistemology)

In essence, Mathison argues this is structurally identical to the Idealist claim: "To know a fact truly, one must know its relation to the Absolute."

This leads to what Classicalists call the "All or Nothing" epistemology [Matt Marino]. According to them, Van Til creates a false binary: either you know the Total System (God's interpretation), or you know Nothing.

This implies that unless you have the "Infinite Cart" (Theology) before the "Finite Horse" (Observation), you cannot go anywhere.

The Thomist argues this is absurd: we do not need to be "sufficiently right about basic presuppositions" to know that fire burns or that 2+2=4. We build from partial knowledge to fuller knowledge.

As such the Thomist argues that Van Til effectively destroys the distinct essence of created things. If the elephant has no meaning apart from God, does it even have a nature? The Thomist fears that Van Til's system turns the creation into a "shadow" of God with no solidity of its own, essentially collapsing the Creator-Creature distinction from the other side, the very Creator-Creature distinction Van Til tried to protect so dearly!

The Presuppositional Surrejoinder: The Impossibility of Neutrality

The distinction between the order of being and the order of knowing, and the "Artifact Analogy" that supports it, collapses because it does not merely distinguish, but attempts to sever the Essence of a thing from its Origin in God’s decree.

Furthermore, the philosophical charges of Idealism and Omniscience leveled by the Realist fail to grasp the theological nature of the Presuppositional claim.

Here’s why:

The Failure of the Artifact Analogy (The Creator-Creature Distinction)

The Realist's analogy of the watch on the beach fails because it ignores the absolute distinction between a human craftsman and the Divine Creator. I.e., God is not a Creator like a human watchmaker is a creator:

A human watchmaker forms a watch and leaves it; the watch does indeed possess independence from its maker. It does not cease to exist if the human maker ceases to exist. It is not dependent on the human maker to continue working, and it can to a large extent be independently studied to figure out exactly why and how it was made, and it can be reproduced.

However, God does not merely "form" the universe and leaves it (like the human watchmaker). He is not a deistic God. Rather, He actively sustains it moment-by-moment. If God were to withdraw His power, the elephant would not remain an elephant; it would vanish into nothingness. Thomist would agree with this: Aquinas wrote that "...it must be said that as the light ceases at once when the sun is eclipsed, so the being of every creature ceases if the divine operation cease." [Summa Theologiae, Part I, Question 104, Article 1]

Therefore, the elephant's "essence" is not merely its biology or taxonomy. Rather, its essence can be described as "Dependent Revelation." To claim to know the elephant as a self-sustaining essence is to know a fiction. As Herman Bavinck noted, "The idea of the origin of things is inseparable from the idea of their nature. If the first is wrong, the second cannot be right." [Reformed Dogmatics]

Consider a sunbeam hitting the floor. A scientist could analyze the beam, measuring its heat, diameter, and photon count. He could describe the beam accurately in every physical detail. But if he defines the beam as a "self-contained cylinder of light" that exists independently of the sun, he has fundamentally misunderstood what the object is. A sunbeam is not an independent object; it is a continuous emanation. It has no existence of its own; its existence is entirely derivative.

Similarly, the elephant has no "Aseity" (self-existence). It is not a noun that sits on a table; it is a verb: a "speech-act" of the Creator.

Refuting the Order of Being/Knowing Distinction

The Realist relies heavily on the distinction between the Order of Being (God is first) and the Order of Knowing (Creatures are first). Van Til rejects this distinction as unbiblical.

Adam's Knowledge

In the Garden, Adam did not know the animals before he knew God. He was created in an atmosphere of revelation. He knew God in and with the world immediately and intuitively (Sensus Divinitatis).

Simultaneous Knowledge

There is no "neutral zone" where man knows finite objects before he knows God. God and the world are known simultaneously, with God as the necessary context for the world. To strip God away is to strip the context away, leaving not "knowledge," but "suppression" [Reformed Forum, "The Christian Philosophy of Knowledge"].

For example, if you grant that the elephant is intelligible on its own terms (as a biological entity operating in a neutral vacuum (i.e. the natural world is self-contained)) you have effectively defined reality as self-sufficient.

You have established a universe where things exist and have meaning regardless of whether God exists. To then argue "Therefore, God exists" is to attempt a logical magic trick. You are trying to derive Absolute Dependence (God) from Absolute Independence (Brute Facts). You cannot start with a premise that assumes God is unnecessary for meaning and legitimately end with a conclusion that God is the necessary condition for existence.

Consequently, if you start with a brute fact, you will never reason your way to the true God; you will only reason your way to a finite "god" who is merely a part of the same system as the elephant. This "god" is not the Creator of heaven and earth but a "god of the gaps"—a hypothesis posited to explain the currently inexplicable parts of the autonomous system. He becomes a "Super-Cause" located within the created order, rather than the Transcendent Sovereign who gives the order its existence.

The Rejection of Neutrality (No Brute Facts)

By claiming that we can know the watch (or the elephant) fully without the Maker, the Realist treats the object as a “Brute” Fact.

This grants the object (and the knower) Autonomy. It suggests that meaning is inherent in the object, rather than derived from God. To treat the elephant as a "neutral" fact is to agree with the atheist that reality is self-contained.

True knowledge is "thinking God's thoughts after Him." God knows the elephant as "My Creature, sustained by My Word." If the atheist thinks of it as "Independent Nature, sustained by Chance," they are not thinking the same thought. The atheist is not thinking analogically (re-interpreting God's thought); he is thinking univocally (creating his own autonomous definition).

Refuting the Charge of Idealism

The Realist accuses the Presuppositionalist of borrowing from British Idealism (the philosophical view that reality is a mental construct where meaning depends on the "whole"). They argue that by linking the elephant's meaning to God's system, we deny the reality (essence) of the elephant itself.

Theological vs. Philosophical Holism: Presuppositionalists do not assert that the human mind constructs reality or that relations are purely logical (Idealism). We assert that the Divine mind constitutes reality. The elephant is not an "idea" in a system but it is a "word" spoken by the Creator.

The Realist argues that "Epistemological Holism" (the idea that the nature of a part is determined by its relation to the whole) was invented by Idealists like F.H. Bradley. They claim that you cannot "borrow" this Holism without also borrowing the Idealist Absolute—an impersonal, pantheistic mind that erases individual distinctions. (Remember In Idealism, relations are "internal" to a logical system. If the elephant is defined entirely by its logical relations to the rest of the universe, it has no independent "substance" of its own. It ceases to be a separate entity and becomes merely a "mode" or "aspect" of the Whole. It dissolves into the Absolute.)

This objection fundamentally misunderstands the difference between Logical Absorption and Creative Definition:

The Bible teaches that God has a sovereign plan. Every fact is related to every other fact because one Mind thought them all up together.

Unlike Idealism, where the part dissolves into the whole, the Christian view asserts that God creates distinct natures by His decree.

Consider a character in a novel, like Hamlet. Hamlet is defined entirely by Shakespeare's mind. There is no "Hamlet" apart from the author's intent. Yet, does this mean Hamlet has no distinct character? Does he dissolve into Shakespeare? No. Shakespeare's creative will gives Hamlet a distinct essence, personality, and history.

Similarly, the fact that the elephant is defined entirely by God (the Whole) does not dissolve the elephant; it secures the elephant. Its essence is derivative, yes, but it is real because God's decree is real.

Thus, when Van Til says, "I know a fact truly to the extent that I understand the relation such a fact sustains to the plan of God," he isn't copying the counterfeit (Idealism). He is pointing back to the Original (Providence). He is saying to the Idealists, "That interconnectedness you see? That isn't an impersonal philosophical grid; that is my Father's world." We do not need to import Holism from philosophy, we need to reclaim it from the secularists who borrowed it from God and stripped His name off the deed.

Idealism argues for "Internal Relations" based on abstract logic. Presuppositionalism argues for Covenantal Relations based on personal lordship. We are not saying you must know the whole universe to know the part; we are saying you must acknowledge the Owner to know the Property. To strip the owner's name off the deed is not "realism"; it is theft.

Refuting the Omniscience Charge (The "All or Nothing" Fallacy)

The Thomist argues that if we must know a fact's relation to God to know it truly, and God is infinite, then we must be omniscient to know anything. They argue: "If you can't know the elephant without knowing its place in God's plan, and God's plan includes everything, then you must know everything to know the elephant."

Van Til addresses this directly: "Suppose that I am a scientist investigating the life and ways of a cow... Complete knowledge of what a cow is can be had only by an absolute intelligence, i.e., by one who has, so to speak, the blueprint of the whole universe." [A Survey of Christian Epistemology]

But he continues with the vital distinction: “But it does not follow from this that the knowledge of the cow that I have is not true as far as it goes. It is true if it corresponds to the knowledge that God has of the cow."

To understand this, we must replace the Realist’s "All or Nothing" binary with the distinction between Archetypal (God's) and Ectypal (Man's) knowledge. Consider the analogy of a construction site:

The Blueprint (Archetypal Knowledge): The Architect holds the master plan. He knows the ultimate position and stress-load of every single brick in the skyscraper. This is Comprehensive Knowledge.

The Brick (Ectypal Knowledge): A worker picks up a single brick. He does not know where this brick will ultimately end up in the skyscraper. He does not have the Master Blueprint.

The Realist objects: "Van Til, you are saying that unless the worker has the Master Blueprint (Omniscience), he doesn't know he is holding a brick!"

Van Til answers: "No. I am saying the worker does not need the Blueprint to know the brick; he simply needs to acknowledge the Architect."

To make the distinction clear:

The Christian View: By acknowledging the Architect, I know this object is a Brick—a created thing designed for a purpose and that it fits in this particular place in the building. My knowledge is partial (I don't know the whole plan), but it is true (I know what the object is and part of its purpose). I know the brick must be placed here, and that it forms part of a greater coherent structure.

The knowledge I do have of the brick is more than what I grasp now, and maybe one day I’ll understand the fuller picture when I catch a glimpse of the complete structure.

The Atheist View: By denying the Architect, the atheist is forced to define the object as a clump of dried clay (Brute Fact). He may know its chemistry perfectly, but by stripping it of its teleology (design), he has fundamentally misidentified the object. Moreover, he has no guarantee that if he places this clump of clay here or there that it would serve any purpose whatsoever.

The knowledge the atheist has floats on a sea of epistemological Chance. He cannot guarantee that it will remain fixed, nor can he guarantee that it will be conducive to anything else, nor can he guarantee that it is related to anything else in a meaningful way.

As such, the Presuppositionalist doesn't claim we need to be the one who has the blueprint (God) to know the cow. Just that we need to be looking at the cow according to the blueprint—as a designed, dependent creature. To deny the blueprint is to deny that the cow is a "cow" at all, reducing it to a random configuration of matter.

The Argument from Infancy (Intuitive vs. Discursive Knowledge)

The Realist often counters with the case of infants or those lacking cognitive capacity: "Surely an infant knows what a bottle is without propositionally acknowledging God Does the Presuppositionalist claim infants know nothing?"

Knowledge is Constitutional, Not Just Propositional: This objection assumes that "knowledge" is limited to discursive, linguistic propositions (e.g., "I believe X because of Y"). However, the Covenantal view asserts that man is constitutionally religious. He is made in the Imago Dei.

As Calvin taught, the "seed of religion" is implanted in the human heart. Infants are not "blank slates" waiting to reason their way to God; they are covenant creatures created in an atmosphere of revelation. They are in immediate, intuitive contact with God's reality.

The Mother Analogy: Consider an infant nursing. The infant knows its mother—her scent, her comfort, her presence—long before it can propositionally articulate "This is my mother" or understand her DNA.

Does the infant experience a "neutral biological organism" that it later concludes is "Mother"? No. It experiences "Mother" directly and intuitively. The relational context is primary; the propositional definition comes later.

Similarly, the infant experiences the world as God's world immediately. They do not start with "neutral brute facts" and later add God; they start in the Father's house. The fact that they cannot yet speak the Father's name does not mean they are autonomous; it means their knowledge is intuitive rather than discursive. They are the ultimate proof that we are made for God, not that we start neutral.

The Witness of Acts 17 (Mars Hill): This is powerfully illustrated in Acts 17, where Paul addresses the Athenians about their "altar to the unknown God." Despite their creation of elaborate pantheons of gods and philosophical explanations for the world, they still felt the unwavering need to acknowledge an unknown deity. They had a sense of a God beyond their comprehension that they could not escape.

Paul did not start with "neutral" facts to prove God; he started with their own worship to expose their suppression. He declared the God they were already worshipping in ignorance—the God in whom they "live and move and have their being." He wasn't building a bridge from a neutral shore. Rather, he was showing them they were already standing on God's ground.

The Color Green Analogy: A simpler way of thinking about this is by considering the experience of the color "green". We might know or experience "green" well before we’re able to acknowledge the concept of "light", which makes the perception of "green" possible. But this does not change the fact that we do know "light" very intimately as soon as we know "green", as "green" presupposes "light".

This is exactly what the Scriptures communicate as well regarding the knowledge of God: "For with you is the fountain of life; in your light do we see light" (Psalm 36:9). God serves as the ultimate context (or atmosphere) in which we live and think. Our knowledge of Him is immediate and arises alongside our earliest experiences of self-awareness and creation in general.

Starting with a Lie (The Eve Paradigm)

The Thomistic "Order of Knowing" has started with a lie. By assuming the effect is intelligible without the Cause (not the capital C), you have surrendered the foundation of knowledge before the debate has even begun.

The Eve Paradigm: Van Til identifies the temptation of Eve as the original "neutral" epistemological experiment. Satan tempted Eve to decide the question of truth ("Did God say?") by using her own autonomous reason as the ultimate judge. She placed God's word and Satan's word on a "neutral" table and used her own mind to weigh the evidence. By assuming she could judge God's word, she had already fallen into the presupposition that God is not the absolute Sovereign [Reformed Forum, "The Christian Philosophy of Knowledge"].

The Structural Flaw: Similarly, the Realist places the human mind in the position of ultimate judge. The argument effectively says, "I have determined what reality is (independent of God); now let us see if God fits into this reality." This reverses the biblical dynamic. Instead of the mind submitting to God's revelation to understand the world, the mind demands that God submit to the world's "neutral" evidence to be recognized.

The Thomist Counter-Response: Contingency is Not Autonomy

The Thomist argues that this Presuppositional attack is a straw man that relies on philosophical confusion. They contend that the Presuppositionalist fails to recognize a massive distinction between a Brute Fact and a Contingent Fact. This distinction is the shield the Thomist uses to defend against the charge of autonomy (see the glossary for definitions).

The Shield of Contingency

This distinction explains why the Thomist gets frustrated when the Van Tillian accuses them of believing in "Brute Facts."

The Presuppositional Charge: "If you look at the elephant without presupposing God, you are treating it as a Brute Fact—something that just exists on its own (Autonomy)."

The Thomist Defense: "No! I am treating it as a Contingent Fact. I look at the elephant and see that it is not necessary (it dies, it changes). Because I see it is not a Brute Fact (it demands an explanation), my reason is forced to look for the Necessary Fact (God) that sustains it."

The Atheist says the Elephant is a Brute Fact ("Just there").

The Thomist says the Elephant is a Contingent Fact (Needs a cause) which proves Necessary Fact (God).

The argument does not try to pull God out of a hat. It follows the path of causality derived from this contingency.

Premise: We see things that are contingent (they do not have to exist).

Observation: A universe of purely contingent things cannot explain its own existence.

Conclusion: Therefore, there must be a Necessary Being (one who must exist) to sustain the contingent things.

This is not starting with a "Lie" (autonomy); it is starting with the Truth of Dependent Being—recognizing that the elephant is insufficient to explain itself.

Rejection of the "God of the Gaps"

The Thomist vehemently denies that this leads to a finite "super-cause." The conclusion of the classical arguments is Actus Purus—Pure Actuality, the Unmoved Mover, the Being whose very nature is To Be. This is the transcendent, sovereign God of the Bible, not a Zeus-like figure inside the cosmos.

Receiving vs. Judging

Finally, the Thomist argues that using reason to infer God from nature is not "sitting in judgment" over Him; it is obeying His command to look at the works of His hands (Romans 1:20). The mind is not the Judge; the mind is the Witness receiving the testimony God has inscribed into the very fabric of the elephant. To refuse to use reason to see the Creator in the creature is not piety; it is a refusal to read God's general revelation.

The Presuppositional Counter-Response: The Myth of Neutral Contingency

The Presuppositionalist apologist argues that while the Thomist defense sounds robust on paper, it collapses when applied to the actual situation of the fallen mind and the specific nature of the Creator-creature distinction. The charge is that the Thomist is fighting a battle in a hypothetical "unfallen" world that does not exist.

The Trap of "Neutral" Contingency

The Thomist claims to start with "Contingency" (dependence) rather than "Autonomy" (independence), arguing that recognizing a thing is not self-sufficient is a neutral observation. The Presuppositionalist, however, exposes the hidden assumption by asking: "Contingent upon what?"

The Dilemma of the Unknown Cause: If the Thomist answers, "We don't know yet; the identity of the necessary being is the conclusion of the argument, not the premise," then a fatal concession has occurred. By asserting that the object's nature can be identified before its source is known, you have defined the object as existing possibly by Chance. You have granted that it is theoretically possible for the elephant to exist in a universe where God is not the cause. To allow this possibility, even for the sake of argument, is to validate the atheist's worldview as a coherent alternative rather than a fundamental absurdity.

It is to define possibility apart from God. It is to bring God down to another fact in a greater universe of facts subject to greater impersonal laws.

Validating the Brute Fact: To define an object as "potentially uncreated" or "neutral" for the sake of argument is to grant the possibility that the universe could be a Brute Fact. A brute fact is an uninterpreted, self-existent datum that carries its own meaning. By claiming the elephant is intelligible prior to acknowledging God, the Thomist effectively agrees with the atheist that facts are self-interpreting. This turns the debate into a probabilistic weighing of hypotheses (Chance vs. Design) rather than a clash of worldviews where one side provides the preconditions for the other.

Surrendering Necessity for Probability: Once you grant that the elephant might be intelligible without God (even hypothetically), you have surrendered the necessity of God. You have agreed that "The Elephant" makes sense as a concept before God enters the picture. If the concept of the elephant is coherent without the concept of the Creator, then God is reduced to a "super-addendum"—an optional explanation for a reality that already seems to function on its own. The conclusion of such an argument can never be the Sovereign Lord who "upholds all things by the word of his power"; it can only be a "likely" architect of a reality that is largely autonomous.

The Logical Barrier (Finite Premises Yield Finite Conclusions)

The Thomist argues that we can reason from the finite effect (the elephant) to the Infinite Cause (God). The Presuppositionalist, however, identifies a fatal logical "short circuit": You cannot extract the Infinite from a pile of the Finite.

The Quantitative Fallacy (The Tower of Babel)

The Thomistic method attempts to build a ladder of logic from the earth up to God. You start with a small finite thing (an atom), move to a larger finite thing (an elephant), then to a massive finite thing (the cosmos), and finally infer a "Maximum Being" at the top. But a "Maximum Being" is not God.

If you stack finite boxes on top of each other, you can build a tower a mile high. You can build it to the moon. But no matter how many finite boxes you stack, the tower will never turn into The Sky. It just becomes a very tall pile of boxes. Similarly, reasoning from a finite universe can only get you to a "Super-Finite" cause. It proves a being that is bigger than the universe, but not other than the universe.

You arrive at a "God" who is merely the biggest object in the room, rather than the Creator who built the room. It does not get you to the God of the Bible who places moral obligations upon and stands in judgement over us.

The "Super-Alien" Problem (The Demiurge)

To make this dangerously concrete: Imagine that scientists discover that our universe is actually a high-level simulation running on a hard drive in a laboratory in another dimension, controlled by a super-intelligent alien named "Bob."

The Cosmological Argument is satisfied: Bob is the "First Cause" of our universe. Bob is the "Designer" of the elephant. Bob is powerful and intelligent.

Christianity is destroyed: Bob is not the God of the Bible. Bob is just a creature who happens to be bigger than us.

The Presuppositionalist argues that the Cosmological Argument, because it relies on neutral reasoning, cannot distinguish between the God of the Bible and Bob. If your argument accepts a "Universe-Maker" as its conclusion, you have proved a Demiurge (a worker-god), not the I AM. To get from "Bob" to the Triune God, you have to smuggle in the Bible. And if you have to smuggle in the Bible at the end, you should have just started with it at the beginning.

Conclusion: The Idol Factory Therefore, the "God" of neutral natural theology is always an idol. He is defined by his relation to the universe (as its Cause) rather than by his own self-contained glory (Aseity). By trying to prove God without presupposing Him and bowing before His self-revelation, you end up with a "god" who fits inside the human brain's logic—a finite conclusion to a finite syllogism.

The Ethical Blind Spot (The Hostile Witness)

The Thomist depicts the human mind as a "Witness" receiving testimony. The Presuppositionalist, citing Romans 1, reminds us that the mind is a Hostile Witness.

The unbeliever is not a neutral observer trying to figure out if the elephant is contingent. The unbeliever is a criminal trying to destroy the evidence of the Creator.

By handing the unbeliever a "neutral" method (logic/evidence) and asking him to judge the case for God, the Thomist feeds the sinner's pride. It validates the sinner's delusion that his mind is the ultimate bar of judgment.

The "neutral" method assumes the mind is healthy enough to process the evidence. The Presuppositionalist argues the mind is ethically dead and suppressing the truth. You don't ask a corpse to take a pulse, rather, you preach resurrection.

The Impossibility of "The One Who Is"

The Thomist claims to arrive at Actus Purus (Pure Being). The Presuppositionalist argues that without presupposing the Trinity, "Pure Being" is indistinguishable from "Pure Nothingness" (as Hegel noted) or an impersonal "Force."

Without the revelation of the Personal God as the starting point, "Being" is just an empty abstraction.

Therefore, the Thomist does not arrive at the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob; he arrives at the "God of the Philosophers"—a silent, impersonal concept that saves no one.

The Mechanism of Common Grace: Attainment vs. Restraint

This leads to the vital distinction regarding how the unbeliever knows anything at all.

The Thomist View (Attainment): The Thomist argues that Common Grace grants the unbeliever the ability to attain valid, neutral knowledge via natural faculties. The mind is a neutral tool that successfully grasps the essence of reality.

The Presuppositional View (Restraint): The Presuppositionalist argues that Common Grace does not grant new knowledge to an ignorant person; it restrains the suppression of truth the person already possesses.

Psychologically: The unbeliever knows the elephant is God's creature (Sensus Divinitatis). The knowledge is inescapable.

Epistemologically/Ethically: The unbeliever suppresses this knowledge to maintain his autonomy.

Therefore, when the atheist correctly identifies the elephant, he is not "attaining" a neutral truth. He is failing to suppress the divine truth. Common Grace acts as a muzzle on his rebellion, preventing him from being fully consistent with his insane worldview. He knows the elephant in spite of his philosophy, not because of it.

Thus, the naturalist is like a child who lives in his parent's home while pretending his parents do not exist. He successfully navigates the layout of the rooms (proximate knowledge) not because his theory of "parent-less existence" is sound, but because he tacitly relies on the order his parents established. His practice refutes his theory.

The Beams: The Epistemology of Parasitism

This brings us to the second analogy: The Floor and the Beams.

The Reality: The universe (The Floor) is supported by the Triune God and His decree (The Beams). Without the Beams, the Floor would collapse into chaos.

The Unbeliever: Walks confidently across the floor while shouting, "There are no beams! The floor floats on nothing!"

The Reality of Borrowed Capital

The presuppositional apologist identifies the unbeliever not merely as mistaken, but as an Epistemological Parasite. The unbeliever must "borrow" from the Christian worldview to finance his rebellion.

Logic: He relies on universal, invariant, abstract laws to reason against God. Yet, in a materialist universe governed by chance, such laws are impossible.

Science: He relies on the Uniformity of Nature—the faith that the future will resemble the past. Yet, he cannot justify this uniformity in a random universe.

Morality: He relies on objective "oughts" to judge the God of the Bible. Yet, in a survival-of-the-fittest cosmos, morality is a fiction.

The unbeliever stands on the Christian "Floor" to slap the Christian God in the face. He is borrowing capital—utilizing the gifts of God to deny the Giver.

The Realist Objection: "But the floor holds him up anyway!"

The Realist argues that the floor is objectively intelligible regardless of the walker's belief. The beams hold up the unbeliever because God is gracious, not because the unbeliever is consistent. Therefore, we should appeal to this "neutral floor" to prove the beams exist.

The Presuppositional Rebuttal: "There is no neutral floor!"

If we grant that the floor is "neutral" (that it can be successfully navigated and interpreted without acknowledging the beams) we have surrendered the war.

If we say, "Let's agree that 'A is A' (Logic) is true, and then debate God," we have agreed that Logic is higher than God.

We have agreed that Logic exists "neutrally" outside of God's nature.

We have granted the unbeliever Autonomy.

The apologist’s task is not to join the unbeliever on a mythical "neutral" floor and politely point to the beams. The task is to pull the rug out from under him—to demonstrate that on his own principles, he should be falling into the abyss. The fact that he is not falling is proof that he is suppressing the truth of the beams that he knows, deep down, must be there.

The Roman Catholic Gateway

This brings us to the deepest theological stake in the debate: the charge that the Thomistic/Realist approach structurally mirrors Roman Catholicism and compromises the Reformation.

The Presuppositionalist warns that by allowing facts (Nature) to be interpreted "neutrally" by reason before introducing God (Grace), the Realist inadvertently resurrects the Nature/Grace Dualism of medieval scholasticism.

The Medieval Structure (The Two-Story House)

Thomas Aquinas and the medieval scholastics operated on a specific view of the Fall, arguing that while sin destroyed man's supernatural gifts (the donum superadditum—faith, hope, charity), it left his natural gifts (reason, logic, sensation) relatively intact. This theological anthropology created a "two-story" universe:

Downstairs (Nature): This is the domain of autonomous reason. Here, man can independently build a solid foundation of truth using the "natural light of reason." He can prove the existence of a "First Cause," establish natural law, and interpret the physical world without any need for special revelation or the regenerating work of the Holy Spirit. In this sphere, the Christian and the pagan stand on identical ground.

Upstairs (Grace): Revelation (Scripture and Church Tradition) is added on top of this natural foundation to complete the picture. Grace does not transform the way we know nature; it merely supplements it with higher truths (like the Trinity or Salvation) that reason cannot reach on its own.

The Reformation Correction (The Noetic Effects of Sin)

The Reformers (Calvin, Luther) radically rejected this dualism. They argued for Total Depravity meaning that sin has corrupted the whole man, not just his will or affections, but his intellect as well.

No Unfallen Zone: There is no "Downstairs" where man remains an unfallen rational creature. The mind of the flesh is "hostile to God" (Romans 8:7). The unbeliever is not merely "deficient" (missing the upper story); he is "dead in trespasses and sins" (Ephesians 2:1).

The Rot in the Foundation: The Reformers argued that because the fear of the Lord is the beginning of knowledge (Proverbs 1:7), the rejection of that fear by the natural man renders his foundational reasoning futile. He isn't a rational observer needing a supplement, but he is a rebel needing a resurrection.

The Gateway to Rome

The Presuppositional critique is that the Thomistic/Realist approach unwittingly adopts the Roman Catholic anthropology (the medieval view of the Fall) to support its epistemology. While the Reformed Classicalist theologically affirms Total Depravity, the Presuppositionalist argues that their apologetic method functionally denies it by treating the unbelieving mind as ethically neutral during the debate.

Validating Autonomy: If human reason is competent to judge the existence of God based on "neutral" evidence, then human reason effectively sits on the throne of judgment, and God is placed in the dock. This reverses the biblical order. Instead of the sinner standing before God to be judged, God stands before the sinner to be verified.

Undermining Sola Scriptura: If "Nature" can be rightly interpreted without "Scripture," then Scripture is no longer the ultimate authority for all of life; it becomes a religious addendum restricted to spiritual matters. This mirrors the Catholic view where tradition supplements Scripture, whereas the Presuppositionalist insists that Scripture must interpret nature.

Therefore, the Presuppositionalist argues that the only way to safeguard the Sola Scriptura of the Reformation is to reject the neutrality of the "Downstairs." We must assert that there is no Nature apart from Grace, no Logic apart from the Logos, and no true knowledge of the world apart from the fear of the Lord. To concede neutrality is to hand the keys of the castle back to Rome, admitting that the natural man is capable of arriving at truth apart from the radical intervention of God's grace.

The Neutrality Trap and the Virtue of Circularity

This leads to the final point of contention, which is often wielded as a weapon against the Presuppositionalist: Circularity.

The Realist frequently accuses the Presuppositionalist of circular reasoning ("You use the Bible to prove the Bible!" or "You presuppose God to prove God!"). In response, the Realist attempts to construct a linear, non-circular argument: Evidence → God. They seek to start from a "neutral" starting point—a shared fact, a logical principle, or a historical artifact—and reason step-by-step to the conclusion that God exists.

However, the Presuppositional apologist embraces the circle, arguing that the linear approach is a mirage. The structure is not merely God → Evidence, but God → Evidence → God. We interpret the evidence through the lens of God’s revelation, which in turn confirms the existence of God.

The charge of circularity fails because, at the ultimate level, all worldviews are circular. No system of thought can justify its ultimate authority by appealing to an authority outside of itself, for then that external authority would be the true ultimate.

The Rationalist's Circle: When asked, "How do you know your reason is valid?", the rationalist must use reason to construct the answer. He is using the measuring tape to measure the measuring tape. He presupposes the validity of logic to prove the validity of logic. He cannot step "outside" of reason to verify reason without using reason.

The Empiricist's Circle: When asked, "How do you know your senses convey reality?", the empiricist appeals to future observations ("I'll check again"). He uses his eyes to validate his eyes. He is trapped inside his own sensory experience with no "neutral" vantage point outside of himself to verify it.

The Christian's Circle: Similarly, the Christian appeals to God to validate the knowledge of God. We do not try to prove Scripture by a "higher" standard like archaeology or autonomous reason, for that would make archaeology or reason our God.

Therefore, the distinction is not between "Circular vs. Linear" reasoning (since linear reasoning about ultimate authorities is impossible), but between Virtuous Spirals and Vicious Circles. The question is not "Are you circular?" but "Does your circle make the universe intelligible, or does it collapse in on itself?"

The Christian Circle (Virtuous Spiral): This circle is expansive and coherent. By presupposing the Triune God and His revelation, we gain the necessary foundation to explain everything else.

We presuppose God (The Beams), which explains why the universe has order (The Floor).

This order allows for the possibility of science and logic (Walking).

Our successful use of logic and science then confirms the reliability of our starting point.

The system coheres; it "spirals" outward, granting intelligibility to history, ethics, psychology, and the elephant. It fits the world we actually live in.

The Unbeliever's Circle (Vicious Circle): This circle is corrosive and shrinking. By presupposing Autonomy and a godless universe (Chance), the unbeliever cuts off the branch he is sitting on.

If the mind is merely the product of random evolutionary survival mechanisms, why should we trust its conclusions about abstract truth or metaphysics?

If the universe is governed by chance, why should we trust the uniformity of nature required for science?

The unbeliever's starting point (Chance/Materialism) actively undermines his method (Reason/Science). His worldview devours itself. The more consistent he becomes with his presuppositions, the less he can know. He ends up in the "abyss" of skepticism, unable to justify even the simplest fact.

Conclusion

Realism holds the high ground on Common Sense. It correctly observes that we live in a shared world where atheists are capable engineers, biologists, and mathematicians. It offers a simpler starting point for conversation: "We agree on the facts; let's debate the interpretation." This makes it functionally easier to deploy in casual engagement.

Presuppositionalism, however, wins on truth and consistency. It is the only system that refuses to surrender the Lordship of Christ over the definition of reality. It correctly identifies that "Neutrality" is a myth—a "demilitarized zone" that is actually enemy territory.

The Presuppositionalist position is correct because you cannot defend the Creator by granting the creature autonomy.

If the Realist is right that we can start with "neutral" facts, then God is not necessary for the intelligibility of the elephant. If God is not necessary for the elephant to make sense, then the elephant is a Brute Fact.

If Brute Facts exist, then God is not the Sovereign Creator of all things.

Therefore, the Realist method, if followed consistently, undermines the very Christian Ontology it seeks to prove.

The Thomist is right that the floor holds the atheist up (Common Grace), but the Presuppositionalist is right that the atheist has no right to walk on it (Antithesis). The Thomist points to the atheist’s successful walking as proof of neutrality; the Presuppositionalist points to the atheist’s stolen beams as proof of God. The Presuppositionalist is ultimately right because he refuses to validate the atheist's delusion that he can walk on air.

Ultimately, the reader must decide: Is it better to build a bridge that might collapse under the weight of autonomy, or to stand behind a wall of truth that only the Holy Spirit can breach? The Classicalist chooses the risk of the bridge; the Van Tillian chooses the certainty of the wall.

Discussion