The "One and the Many," a philosophical concept that treads the thin line between unity and diversity, finds an interesting parallel in the domain of video games. In the sphere of procedural generation, this balance, or sometimes the imbalance, becomes even more palpable.

In a procedural generation, the "One" is rooted in the foundational elements predefined by developers. Think of these as the abstract classes, the boundaries set in stone, or the underlying rules that govern the game's universe. These are the constants, the unchanging tenets that provide a framework. Now, enter the "Many." It's where chance reigns supreme, spawning an array of elements that, while adhering to the "One," are generated randomly. So, you might encounter a piece of terrain or a creature, recognize its class or category, and then realize that the specifics (the colour, size, location) are mere products of chance. After a few encounters, the world might start feeling predictable in its randomness, its vibrancy dimmed because the details lack intentionality.

Contrast this with a finely handcrafted game. Here, the the one and the many are more than a mere rigid framework coupled with chance; it's a canvas. Developers paint on this canvas with purpose and precision. While abstract classes might still exist, they are not mere containers for random content. Each item, each element is placed with deliberate intent. Its size, location, colour, and function are chosen to serve a specific purpose in the grand narrative. In this setting, every tree, building, or creature isn't just a representation of its class. It's a unique entity with a distinct role in the game's symphony. If one were to remove an element, it would be akin to plucking a note out of a melody; the experience would be lessened.

People have mulled over the impact of procedural generation in games in the past: A query from a curious Reddit user touched upon this duality, questioning whether procedural generation, with its promise of infinite adventures, could genuinely deliver a fulfilling exploration experience. Also, a study from The Computer Games Journal in 2017 shed light on a pertinent aspect: while procedurally generated content offers vastness, it may lack the depth and engagement that human-crafted designs bring.

A useful thought exercise to understand philosophical systems

The world of video games, especially when dissected through the lens of procedural generation, becomes a microcosm for deeper philosophical explorations. Just as games grapple with the balance between structure and spontaneity, so too do belief systems like Atheism and Christianity (in its various forms like Thomism, Molinism, and Calvinism) wrestle with the intricate dance between determinism and free will, order and chaos.

Atheism, in many ways, mirrors a game governed by pure Chance, where events and structures seem devoid of any overarching intent. Thomism/Molinism, with its blend of predefined classes and chance, can be likened to the procedural generation where there's an underlying order, but much is left to randomness. Calvinism, on the other hand, resonates with the handcrafted game realm, where every detail is meticulously designed with purpose, echoing a universe where every event is divinely ordained.

By delving deep into game mechanics and design philosophies, we find analogies that shed light on some of humanity's most profound philosophical questions. The parallels drawn between game development and these belief systems underscore the universality of the quest for understanding the delicate balance between the One and the Many, intention and randomness, purpose and exploration.

Atheism: The Game of Chance

Imagine booting up a video game where not a single line of code has been deliberately crafted. This is the world of Atheism - a realm where Pure Chance, emphasized with a capital 'C', governs every aspect. Here, Chance isn't merely a random element; it negates the very essence of "intention". At first glance, it might seem as if you can "endlessly navigate" this vast domain, but the intricacy of the issue runs much deeper. In a world shaped entirely by Pure Chance, even foundational concepts such as "you" or "navigation" are ephemeral. Can there truly be a consistent identity or purpose in a universe where everything is transient? It's difficult to imagine a place or video game like this - but this is the logical terminus of atheism.

This is the landscape of the abstract particular, a realm where particulars exist but devoid of any systematic structure. Every action, every thought, every pixel in this virtual world stands isolated, without a coherent framework. The very act of identifying something presupposes a stable reference point, a systemic structure. But in a world dominated by Chance, such reference points are elusive. The identity of "you", the concept of "navigating", and even the ground you tread on are all fleeting, lacking any anchoring intention. It's a world where particulars float, unmoored from any definable system.

The reflections of Ann Druyan, wife of the renowned late atheist Carl Sagan, on life, love, and death epitomize this worldview. Contemplating Carl's death, she wrote: "We knew we were beneficiaries of chance... That pure chance could be so generous and so kind." Yet, when delving deeper into the philosophy of Pure Chance, contradictions arise. To express gratitude or to identify oneself within a narrative implies a consistent self and an identifiable other. How can one anchor such sentiments in a world where particulars stand without a system?

The essence of Pure Chance doesn't merely challenge our understanding of predictability, it erodes the very bedrock of existence. In this realm, every element, every thought, and every emotion becomes unidentifiable, drifting aimlessly in the vast expanse of the abstract particular. This world is like beads with no holes in them such that they cannot be strung together in a system. Each bead becomes an unidentifiable brute fact.

Certainly, a world of Pure Chance is the definition of uninhabitable. If atheism were a video game, it would quite literally have to cease being itself to be able to run on any computer. This is why Christian theologians have written about the "borrowed capital" of atheism. Although those who profess to be atheists have received many gifts from God, they have taken those gifts and did not give due honour to God as their Creator - hence they are living on borrowed capital - assuming things and using gifts that make no sense in their own worldview.

Thomism: The Procedurally Generated Universe

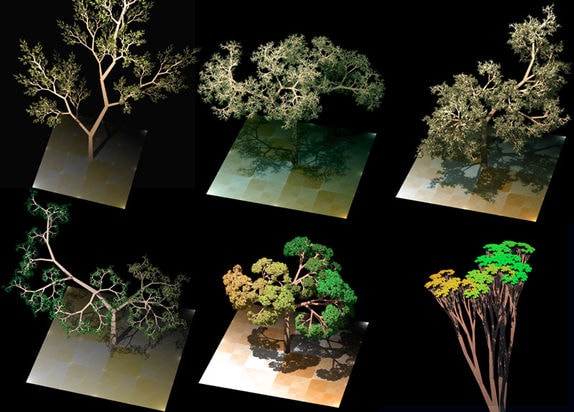

Step into the realm of Thomism, reminiscent of games like "No Man's Sky", "Minecraft", or "Starfield". In these games, the world is procedurally generated. There are preset "classes" determined by the developers, but the unique characteristics or accidental properties of the instantiations of the classes are governed by Chance. This makes exploration an intriguing aspect of gameplay and makes the world actually inhabitable (unlike atheistic video games - as there is an underlying unity that ties everything together). Yet, there's a caveat. While the vastness of this universe encourages players to discover new terrains, it might lack depth. The anomalies, even when they occur, don't necessarily fit into a larger narrative or have any real significance. This randomness can render the world a mere resource-gathering field (as in the case of Minecraft and Starfield), with the discoveries and landscapes feeling devoid of any profound meaning.

Thomism, rooted in the teachings of Thomas Aquinas, presents a fascinating parallel to the concept of procedural generation in video games. To understand the interplay between these philosophical systems and game mechanics, we can break down some of the similarities.

Just as every procedurally generated game is based on a foundational algorithm or set of rules crafted by its developers, Thomism posits an underlying divine blueprint for the universe. Thomas Howe, an Evangelical Thomist writes, "According to the Moderate Realist (Thomistic) view, all things exist in God’s mind before their existence in the finite world of things. God created the matter out of nothing and imposed upon it a form, thereby creating a thing in reality. This creative event is characterized in the Scripture by the phrase, “...and God said.” The resultant real object is composed of form and matter" (Howe, Objectivity in Biblical interpretation)

This foundational logic, whether it be the game's base code or the divine order, sets strict parameters within which the game or the universe unfolds. These can be considered Aquinas' "forms". According to Aquinas, everything that exists (or every substance) is a form/matter composite. "Form" is the principle whereby the matter has the particular structure that it has, and "matter" is simply that which stands to be structured in a certain way. This is called a hylomorphism. Hylomorphism is a philosophical doctrine developed by the Ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle, which conceives of every physical entity or being as a compound of matter and immaterial form. God creates the forms, and matter, and then joins them to form the substance (or creature). The form is the intelligible structure which the mind can abstract and know, and matter is the unintelligible differentiator between substances that are built from the same form.

Just like in a procedurally generated game, a specific framework (form) exists, but the content that spawns within this boundary can differ widely (matter), offering a unique experience with every playthrough. The Thomistic parallel should be clear. While there's a steadfast divine order, there exists room for chance, variability, and individual free will to operate within these boundaries. And so Aquinas has married two fundamentally contradictory principles - pure form and pure chance. Somehow, pure chance and flux serve pure form and vice versa despite the inherent tension that exists between these two concepts when viewed in abstraction.

"The result of the application of a pure form to pure matter is a meaningless interaction between an abstract principle of rational determinism and an equally abstract principle of irrational indeterminism. For Aristotle (and Aquinas), knowledge is by means of universals only. There is accordingly, for Aquinas, no knowledge of the changing course of nature and history" writes Cornelius Van Til in The Case for Calvinism.

For example, in Minecraft, the world is procedurally generated. There are certain parameters set by developers (e.g. possible biomes and types of animals). As the player progresses through this world, they are acutely aware of the "form" of each biome and animal as they explore the world, but they are also aware that whenever a biome or animal appears, there is nothing in this particular biome or animal that contributes something to their existing understanding of the "form" of the biome or the animal. All they perceive are new, chance-generated accidental properties.

We must, to be sure, think of pure form at the one end and of pure matter at the other end of our experience. But whatever we actually know consists of pure form and pure matter in correlativity with one another. Whenever we would speak of Socrates, we must not look for some exhaustive description of him by means of reference to an Idea that is “wholly beyond.”

Socrates [a person] is numerically distinct from Callias [another person] because of pure potentiality or matter. Rational explanation must be satisfied with classification.

The definition of Socrates is fully expressed in terms of the lowest species. Socrates as a numerical individual is but an instance of a class [human].

Socrates may weigh two hundred pounds and Callias may weigh one hundred pounds. When I meet Socrates downtown he may knock me down; when I meet Callias there I may knock him down. But all this is “accidental.” None of the perceptual characteristics of Socrates, not even his snub-nosedness, belong to the Socrates that I define.

By means of the primacy of my intellect I know Socrates as he is, forever the same, no matter what may “accidentally” happen to him. And what is true of Socrates is true of all other things.

Cornelius Van Til and Eric H. Sigward, The Articles of Cornelius Van Til, Electronic ed. (Labels Army Company: New York, 1997).

We can note the hypothetical impact on the human experience of this worldview. Knowledge, according to Aquinas, is of the forms or universals only. This makes intuitive sense, as the properties informed by matter are accidental. Thus, when a person sees an apple and abstracts the form of "apple", they have exhaustive knowledge of what an "apple" is. When you've had an experience with an "impala" in the Kruger National Park, you've already abstracted the form of "impala", and as such there's nothing more to gain from observing more impalas (apart from observing more and more accidental properties exemplified in various impalas). Thus, Aquinas' account of knowledge makes the idea of exploration beyond the first instance of a class superfluous. We see this in Minecraft as well. No one explores the world in Minecraft to appreciate the landscapes. Exploration is merely a means for the player to gain more resources. This makes the world fundamentally uninteresting. Yet, this is not our experience of the real world. When you enter the Kruger National Park and see the first impala, you are interested in seeing more impalas as each of them is surely more than just a mere substance and accident.

There is still much to write on the Thomistic account of knowledge and universals - and we have discussed this at length in other articles on the website. Read more: Back to Basics: A Reformed perspective on natural theology beyond Thomsim.

Molinism: Another Procedurally Generated Universe

Molinism, rooted in the ideas of the 16th-century theologian Luis de Molina, seeks to reconcile God's overarching sovereignty with the free will of humans. While our examination of atheism and Thomism largely centred on metaphysics — the inherent structure of reality — our exploration of Molinism, through the lens of video games, will be tethered more to historical unfoldings and events.

Dr. Tim Stratton, in his dissertation on Mere Molinism, called "Human Freedom, Divine Knowledge, and Mere Molinism: A Biblical, Historical, Theological, and Philosophical Analysis", introduces the term "Exhaustive Divine Determinism" or EDD. Stratton critiques EDD, positing that while certain elements might be under divine determination, not everything is. This idea resonates with the design mechanics of games like "Starfield", where specific story arcs or locales are predetermined, but vast expanses of the game arise from procedural generation, ensuring a unique experience each time it's played.

In this model, God, akin to a game designer, crafts a world grounded in a core vision. He sets foundational parameters, ensuring specific divine objectives are achieved. Yet, beyond this, God grants space for variability — what might be termed as Chance. Stratton's perspective attempts to uphold human agency and moral responsibility. He seeks a framework where instances of moral evil don't "implicate" God in direct causality, especially in the case of natural disasters, conflicts, and atrocities.

However, Stratton's stance prompts challenging questions for the Christian thinker. If not from God, where does this element of Chance emerge? Although Molinism posits that God selects the most optimal of possible worlds to realize, the presence of evil, even if by "Chance," remains a theological quandary. Who, or what lays out these potential worlds for divine selection? What has the power to independently impose things on God? This is a scary thought, and ultimately, when consistently worked out - implies an atheistic view of the world. God, like us, becomes a mere player in a world governed by brute fact and Chance.

Moreover, such a perspective could risk sapping life's events of deeper significance. If experiences, whether joyous or tragic, are ascribed to mere Chance within a divinely chosen world, does this not make life's tapestry seem arbitrary? Just as a player might find the procedurally generated expanses of Starfield void of deeper intent and narrative, so too might one view life's events under Stratton's model: rich in variability, but potentially lacking in meaning.

Calvinism: The Crafted Masterpiece

Step into the realm of Calvinism envisioned as a game where every element — from individual pixels to vast landscapes and intricate character interactions — is deliberately designed. In this world, exploration becomes an exhilarating experience. Each stone, structure, or secluded nook beckons, driven by the knowledge that everything exists with a distinct purpose. The game unfolds with a depth of narrative and continuity that engenders a perpetual sense of awe. Players in this environment aren't simply meandering through random occurrences; they're uncovering the meticulous craft of the Game Developer, immersing themselves in a universe where each moment bears significance and is interconnected.

Consider "Red Dead Redemption 2" (RDR2) as an illustrative example. This game stands as a testament to intricate design, with Rockstar, the developer, renowned for the immense detail and hidden surprises woven into its virtual landscapes. While certain random events punctuate the gameplay, the overarching design feels intentional and deliberate. Yet, it's crucial to remember that we're drawing on game development as a metaphor, an illustrative tool to elucidate Calvinistic concepts, as such, the claim is not that RDR2 has no elements that rely on chance.

In the Calvinistic world, there is no Chance. There is chance from our perspective (lower case c) - as some events seem inexplicably occur, but this is called "chance" from our perspective, simply because we lack a "Gods-eye" view of the world, there are no brute facts.

In the Calvinist perspective, the world is teeming with variability, but not devoid of profound meaning. Take the example of an impala in the Kruger National Park. This creature isn't a mere product of Chance as one might infer in an atheistic worldview. If it were, our identification of it (and even of ourselves as subjects who identify the object) would be impossible. Moreover, an impala isn't just a representation of a "form" as posited in Thomistic thought, it embodies more depth and nuance.

Within the Calvinist system, knowledge operates on two foundational tiers: the knowledge belonging to the Creator, and the knowledge accessible to the creature. From the Creator's vantage point, an impala isn't just another member of its species. God perceives this specific impala within a vast, interconnected tapestry of creation. Every detail about this impala, its role in the larger ecosystem, its contribution to the grand narrative of the world, and its intricate relationship to everything else is known to God with precise clarity.

Contrast this with our human experience. When we, as creatures, encounter an impala, our understanding is inherently limited. We might categorize and recognize patterns among various impalas, yet our knowledge isn't static like the unchanging "forms" of Thomism. With every observation, our comprehension deepens. An initial encounter might provide a basic notion of what an impala is, but as we observe more, unexpected characteristics emerge, refining and expanding our understanding. This is one of the key reasons we never seem to tire of this world. Even elderly people in the park enjoy sitting in the same sun every morning, feeding the same kind of birds. This is because each day isn't merely the replay of the same static truths mixed in with Chance, each day is really new, yet with a profound continuity, variability and meaning.

Calvinism presents a distinctive resolution to the enduring philosophical quandary of the one and the many that have persisted since the era of the pre-Socratics. Instead of prioritizing either the one (as Thomism does) or the many (as atheism suggests), Calvinism posits that both are equally fundamental and harmoniously interconnected. This reflects on a creaturely level the eternal One and Many of God the Trinity. I.e., in God, there is one essence and three persons, all equally God. God's diversity is not more ultimate than His unity (as if the three persons merely combine to form God), and His unity is not more ultimate than His diversity (as if the three persons [in this case three separate gods] emanate from the one essence or the Father alone). In the same way, yet on a creaturely level, the particular impala is not more fundamental than its class, nor is the class more fundamental than the impala. They are both equally ultimate and related in God's single comprehensive plan for the world.

The creature's perspective serves as the proximate foundation for all knowledge. Our understanding is rooted in the comprehensive knowledge of God, which underpins all existence. Given that all facts are interconnected through God's eternal design, our current, limited knowledge is coherently linked to the unknown facts we'll come to grasp in the future. This protects us from scepticism (scepticism being an issue that plagues the atheists, Thomists and Molinists due to their capitulation to Chance). Read more about this here: Reformed Thomism: Ultimate and proximate differences and starting points.

Finally, an objection might be raised against the Calvinist: Doesn't Calvinism destroy human freedom? Surely the reason the Thomist and Molinists allow for Chance is to secure human freedom and moral culpability? The answer is that paradoxically, God's decree establishes human freedom and responsibility rather than removing it. It is when Chance is allowed that the identity of the person is destroyed and along with it moral culpability. Read more here: Calvinism, human free will, and divine sovereignty explained

As we can see, there is much more to explore and debate when comparing various systems of thought, and no doubt that this article did not answer every single question, but it served its intended purpose of attempting to contrast various systems of thought using video games as an example.

Conclusion

The problem of the one and the many, a philosophical quandary about unity and diversity, can be brilliantly illustrated using video games. Each game represents a different system of thought, offering players varying experiences based on the nature of its creation. While the realm of Atheism may seem chaotic and the world of Thomism vast yet random, Calvinism offers a journey filled with meaning and intention. Through these game analogies, we can grasp the essence of each philosophical system and the worldviews they present.

Discussion