In a recent debate with an atheist online, I was in the process of demonstrating the impossibility of the atheist "worldview" ( I say worldview in quotations because some atheists might take issue with its use here - this is not important for the article). I was pushing the particular atheist to account for the preconditions of knowledge, some of which are:

Reliability of reasoning

Reliability of senses

Laws of Logic (universal, unchanging, transcendent and immaterial)

Reliability of Memory

Suddenly, out of nowhere, another atheist shows up and exclaims: "He's a presuppositionalist! Don't worry I got this." He probably felt like a superhero at that moment jumping in to save his brethren. So how did he handle my charge that the atheist needs to justify the preconditions of knowledge? - "Those are my base axioms and hence they need no justification!" he said.

Axioms

An axiom is a statement or proposition which is regarded as being established, accepted, or self-evidently true.

Now, this has always been a part of presuppositionalism that has been widely misunderstood by unbelievers and our classical brothers alike. Saying that the preconditions of knowledge are your axioms or that you assume them does not bring anything new to the table. We all assume those things, that's not the point that the presuppositionalist is arguing. We are not saying that atheists cannot reason, use the laws of logic or trust their senses. We are saying they cannot give an accounting for that assumption. Why? Because their epistemology conflicts with their view on ontology.

Ontology is the study of the nature of something, It addresses what kinds of things exist.

Epistemology is the study of knowledge - how we know what we know.

There seems to be a movement in modern philosophy that completely divorces ontology and epistemology, but this is unwise. For example, if our epistemology endorses the use of laws of logic in reasoning, then it would be ridiculous for our position on ontology to reject the existence of laws of logic.

Ontology cannot be divorced from epistemology. The transcendental argument points out that if knowledge is possible (an epistemological premise), then God must exist (an ontological claim) since the biblical God is the basis for knowledge (a Scriptural claim).

No unbeliever can account for the existence and properties of laws of logic, morality, or uniformity in nature on his own professed worldview. His epistemology is rationally unjustified and in tension with his position of ontology. This is necessarily the case since all knowledge is deposited in Christ (Col. 2:3).

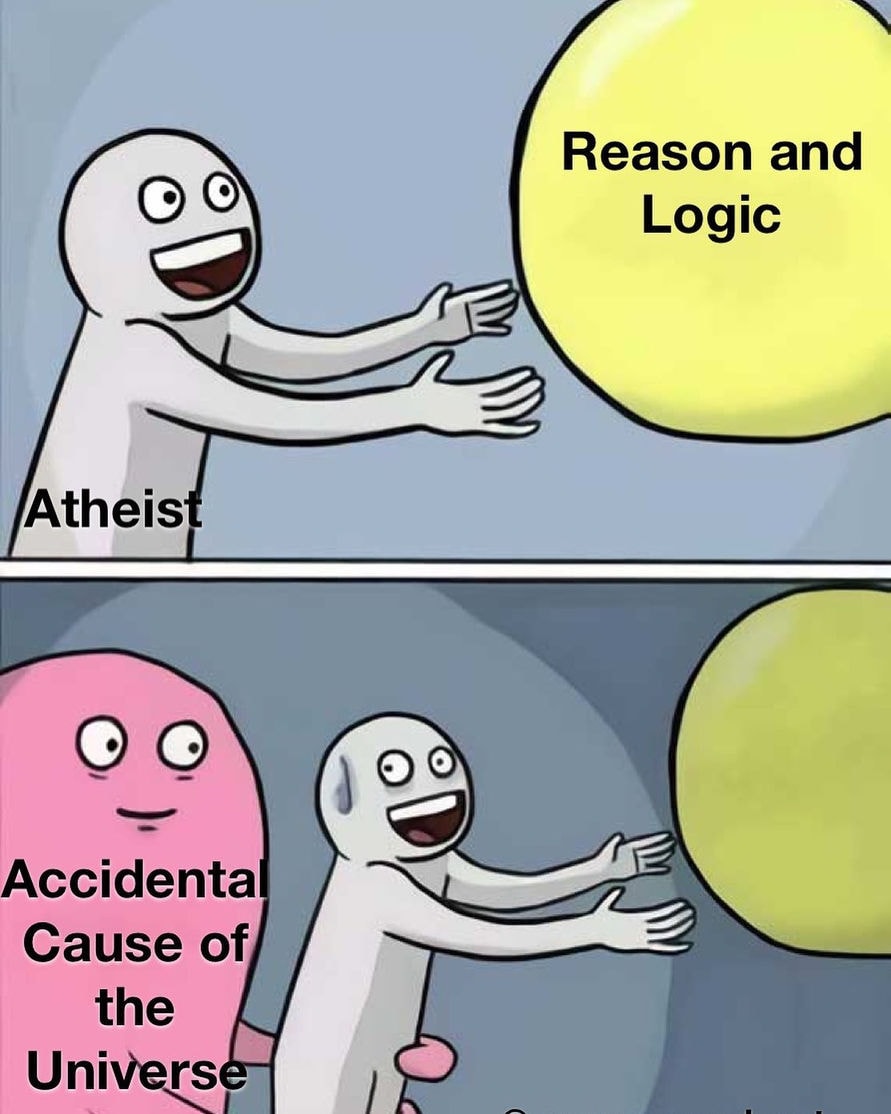

To make this more tangible, the atheist and the Christian assume the preconditions of knowledge every single second of the day. Yet what the atheist professes to believe comes in conflict with his assumptions. The atheist doesn't serve Christ in whom all knowledge is deposited but rather embraces and naturalistic and materialistic view of the world. The atheist believes we're a cosmic accident. But this view of the universe cannot make sense of immaterial, universally applicable, transcendent and unchanging laws of logic. Therefore to remain an atheist, the atheist needs to reject the laws of logic (or at least the properties that make them laws of logic), but here's the kicker - you can't reject them without using them (what use is it to reject the classical attributes of the laws, and still hope your rejection carries any meaning for anyone except you?), therefore, the atheist worldview falls flat. This is what is meant by the atheist's ontology conflicting with his epistemology.

Remember, the atheist rejects the God of the Bible who created and pre-interpreted all of reality. If it is the case that man's interpretation of the world around him is wholly original, there's no way to escape the problem of subjectivity in the thought of each individual person. In addition, the idea of brute fact (uninterpreted facts that result via a principle of chance) has no reason to provide uniform experience, unchanging laws of thought, or universally applicable laws of thought such that each person ought to reason in a particular way. Even if the atheist gives up the classical attributes of the laws of logic and falls back on something like "my laws of logic", he enters into the realm of subjectivity and ultimately scepticism, simply because the unbeliever cannot deduce from his laws of logic alone their applicability to the external realm to which he brings them to bear.

However, there is a different problem that plagues the person who doesn't want to go further in their justification for the preconditions of knowledge than simply saying that they assume them to be true.

Arbitrariness

Arbitrary - based on random choice or personal whim, rather than any reason or system.

If there is no rational justification offered at the end of the day for the assumptions/axioms that they make, who is to stop someone from simply negating those assumptions and declaring everything the person says as garbage? The atheist, therefore, fails to escape subjectivism by appealing to mere unjustified axioms.

The final defence

I articulated this to the particular atheist pointing out the arbitrariness and subjectivism by stating that he could be wrong about everything he claims to know as a result. The answer? 'Yes, I never claimed to know anything'.

And there's the absurdity. At this point, the debate got quite fun. If he could be wrong about everything, could he be wrong about that? Could he be wrong about his belief that he is not a Christian? His answer? 'Yes!'.

For the sake of completion, I opted to make sure he knows the absurdity of his statement. Any proposition someone makes can either be true or false. So the statement "I cannot know anything" can be true or false. If it's true, it's self-refuting as then you know something. If it's false, then well why did you say it cause then you can know things. At this point, the atheist demanded that I demonstrate why a proposition can only be true or false. Why this is by the law of excluded middle which the atheist claimed was his axiom not a few minutes earlier. And there's the contradiction wide open for the world to see.

Discussion