Introduction

Professor Lumumba, who served for several years as the director of the Kenyan Anti-Corruption Commission, delivered the keynote speech at the 3rd Anti-Corruption Convention in Kampala, Uganda in 2013. In his speech, he raised an alarm that one of the main reasons why Africa remains the poorest continent on earth is that the levels of tolerance for corruption in Africa are very high. According to him “Africa has been invaded by its own sons and daughters who are forever looting its resources in the name of governance and democracy” [1]. About the corruption and bribery among leaders, he said: “We elect hyenas and expect them to take care of the goats.” [2] In the speech he raised the question: “Are we children of a lesser God?”

Although he did not explore the relationship between corruption and concepts of God in the mindsets of Africans, his remark indicated the need to consider the relationship between corruption and African concepts of God.

What is corruption?

A standard definition of corruption is the abuse of public or private office for personal gain.

Vishal Mangalwadi, in his book, Truth and Transformation: A Manifesto for Ailing Nations, defines it this way:

Corruption involves abusing one’s power to harass, coerce, or deceive others (individuals, institutions, or the state) to acquire value (money, service, goods, ideas, time, property, or honor) without returning proportionate value to them. [3]

In a survey by Transparency International on People and corruption in Africa it is stated that nearly 75 million people in Sub-Saharan Africa are estimated to have paid a bribe in 2015 [4] – some to escape punishment by the police or courts, but many forced to pay to get access to the basic services that they desperately need.

In his book on the roots of sin, Professor Yusufu Turaki [5] from Nigeria convincingly argues that you cannot kill a tree by cutting off a few of its branches. You need to dig down and cut off its roots. Turaki uses Holy Scriptures as a spade and axe as he digs down to examine the roots of sin. His knowledge of traditional African beliefs and values adds depth to his discussion of the origin, nature, effects and power of corruption in the lives of African people. He shows the relevance of each member of the Holy Trinity to our struggle against the root sins of self-centredness and pride, greed and lust, and anxiety and fear. He listed bribery as one of the outstanding examples of a branch of the deeper lying sin of greed, that is really caused by being alienated from the Triune God of the Scriptures.

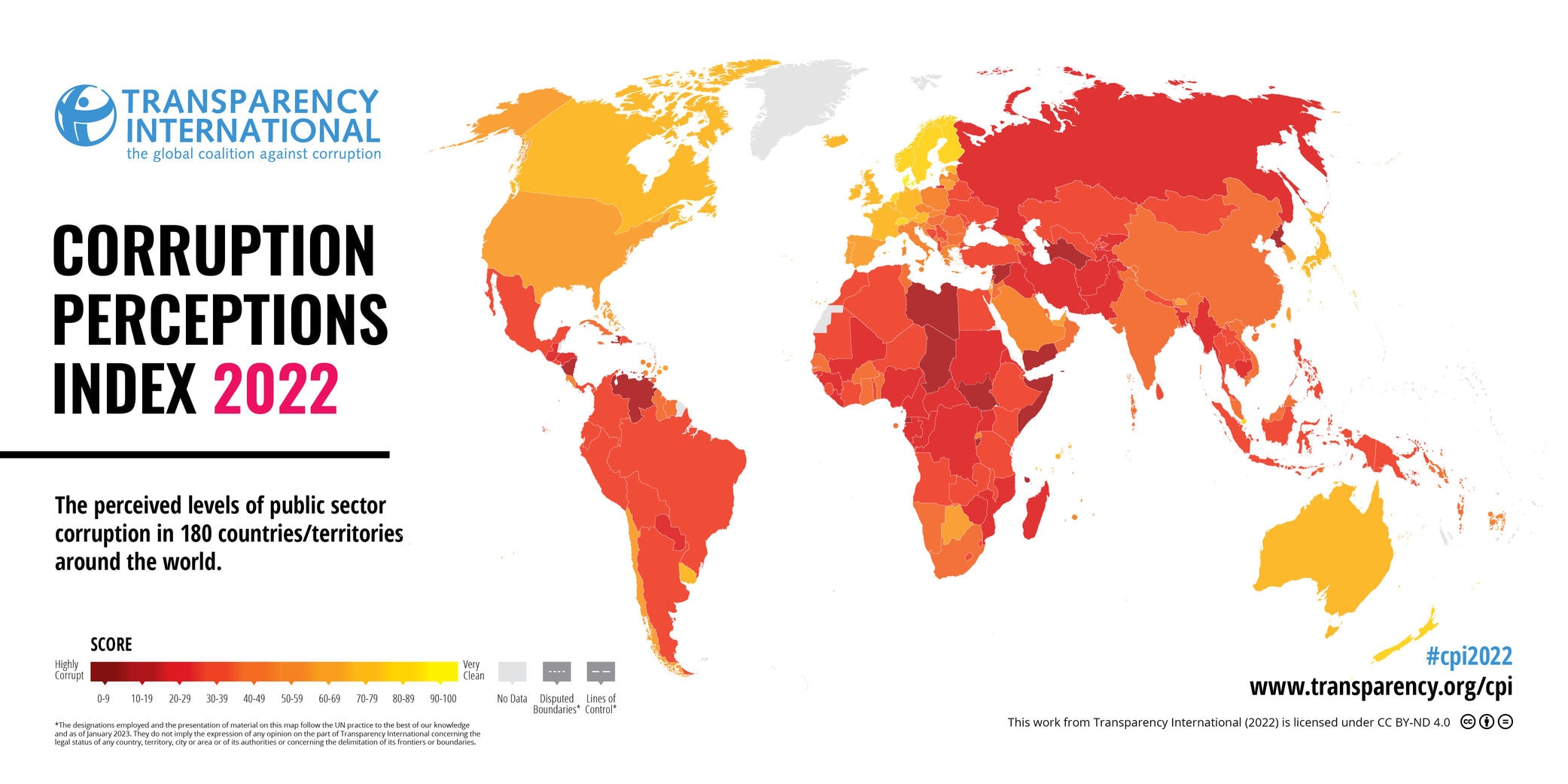

The multiple and embarrassing scales of corruption currently surfacing at the Commission of Inquiry into Allegations of State Capture in South Africa [6] (publicly referred to as the Zondo commission) and other related enquiries, placed the Republic of South Africa ranked 73rd out of 180 countries that participated in a Transparency International (TI) survey. This survey ranks participating countries according to their perceived levels of corruption in the public sector. Based on information emerging from the Zondo commission’s proceedings, political analyst Marianne Mertin recently published an article in which she revealed that State Capture in South Africa during the 2nd term of president Jacob Zuma’s administration, hovers around R1.5-trillion of the Budget for 2019. “Put differently: State Capture has wiped out a third of South Africa's R4.9-trillion gross domestic product, or effectively annihilated four months of all labour and productivity of all South Africans, from hawkers selling sweets outside schools to boardroom jockeys.” [7]

The Corruption Perceptions Index 2018, which gave South Africa a score of 43 out of 100, was shared by Corruption Watch. Corruption Watch’s Executive Director, David Lewis, said that South Africa’s experience of state capture was a textbook example of the relationship between corruption and the undermining of democracy. [8]

In a new report, titled Corruption in Uniform: When cops become criminals, the civil society group Corruption Watch received 1,440 reports of corruption about the police between 2012 and 2018, in South Africa, with instances of bribery, abuse of power, and failure to act leading the complaints. The report released on Thursday, June 13, 2019 analyses the claims lodged against SAPS with the anti-graft group since its 2012 establishment, describing “alarming levels of corruption” across the country. [9]

Even though African leaders declared 2018 as the African year of anti-corruption, that commitment did not translate into concrete progress yet. [10]

Four personal experiences

I have worked for 25 years as a cross-cultural missionary and theological educator in one of the old “homelands” in South Africa. In that homeland, I was told by locals that the tribal king rules over everything. If you want to see him in order to get permission to work in the area, you first had to respect him with a “gift”. I was told: “This is our culture: You won’t get his ears if his eyes have not first seen the gift that you have given to his indunas.”

But then I quickly learned that this rule also applies to all other levels of government. For instance, we once had a youth group from abroad who wanted to come and help a local church to erect a church building. The local church had to find a suitable site in the township. After many struggles for a few months, I could not succeed in finding a site. The local municipality told me that all the sites were already taken. When I told the church that I am going to inform the group from abroad that we’ll have to cancel their trip and drop the plans of their visit, a lady from the church pleaded that we must just give the church one more week to look for a site. After 3 days she phoned me to inform me that she has found a site and that I must go with her and the treasurer of the church to the municipal offices to fill out all the necessary documents and pay for the site. When I came there, we filled out all the formal documents to buy the site that was sold for a very reasonable price. When we got ready to depart, the official asked the lady: “Now when do I get my ‘cool drink’ money?” I then realized that she secured a site for building a church by offering to pay the municipal clerk a bribe.

An African pastor in another township told me that his church had to pay a bribe to a municipal councillor of the ruling political party of the township to receive a site to erect a church building and an orphanage that they were planning to serve their community.

I once travelled by car from South Africa to Lubumbashi in the DRC to participate in a conference. A friend warned me to make extra copies of all the car’s official documents and take them along. He had an experience where his documents “disappeared” when he handed them in at the customs office at the border and then had to pay a bribe to be allowed entrance into the country. I am glad that I was forewarned because I then had the same experience. At the one counter at the customs office, the official requested documents for my car and instructed me to go and wait at the next counter. At the next counter, the official again asked to see the documents of my car. When I told him that I have handed them in at the previous counter he said that he has not received them and made it clear that the problem could be solved with some “cool drink” money. He was not happy when I pulled another set of copies of the documents from my bag and handed it to him, and he had to let me proceed without paying him “cool drink” money.

Many more such experiences in Zimbabwe, Zambia, Kenya, Uganda, Rwanda etc. taught me that the culture of bribery and corruption is deeply rooted in Africa. Considering the roots of these practices led to my research on the worldview and especially the concepts of God in the traditional African worldview that are some of the roots of widespread bribery and corruption.

Corruption and bribery surface in different ways in different cultural groups resulting from different worldviews

Several authors have revealed the influence of worldview and culture on poverty, corruption and bribery in different parts of the world [11] but pointed out that it grows from different roots in various cultures.

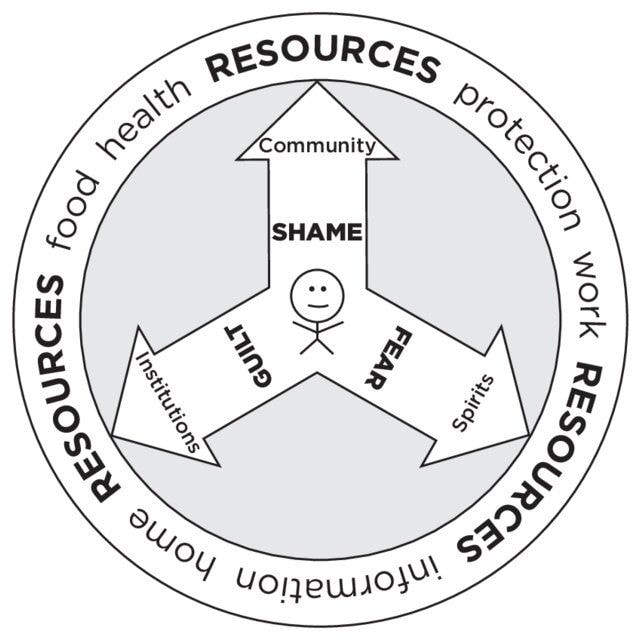

Jayson Georges [12] explained that guilt, shame, and fear in the worldview of people are the moral emotions that they use to organize the distribution of resources between people. With the circle illustration below Georges visually depicts how a person (in the centre) acquires essential resources (the outer ring), and the three potential emotional barriers.

Dr Tom Julien, Executive Director Emeritus of Encompass World Partners summarized it well in his endorsement of the book of Jayson Georges:

Sin is the universal malady of mankind. For some cultures sin brings guilt; others feel shame; still others, fear. An understanding of the roots of the symptom provides the path to the solution, the Lord Jesus Christ. [13]

It is not the intention of this article to make a comparison between African and Western European, or Asian ethics, corruption and bribery. I do not regard traditional European ethics as superior to traditional African ethics. On the contrary, the influence of modem European ethics, with its deeply ingrained individualism and disregard for the value of the community and for parental authority, is to be regarded as a serious threat. There is also truth in the arguments that colonialism was a selfish exploitation of the wealth of Africa. [14]

Reports of Transparency International also reveal even worse statistics of corruption and bribery in other parts of the world. The fact that European and Asian ethics are not criticized in this article, does not point towards any admiration for those, but merely means that they fall beyond the scope of this article.

In the graph of the corruption index of Transparency International below it can clearly be seen that corruption in many countries is worse than in South Africa and other African countries. [15]

In several research papers Heather Marquette [16] came to the conclusion that academics and activists are unlikely to be able to prove a direct causal relationship between religion and corruption – either positive or negative – and certainly not with the methodologies employed so far. She does acknowledge that in many parts of the world, religion maintains a primordial hold on people’s values, attitudes and behaviour that democratic institutions simply do not, and as such, it remains an important potential source of power.

Unfortunately, she failed to do intensive research on aspects of the African traditional worldview and especially concepts of God that may open the way for corruption and bribery.

This article, then, explores how the traditional African mindset determines the nature and extent of African responses and views about life in general, but specifically how African concepts of God provide roots for corruption and bribery. In this regard, it is important to recognise that religious mindsets and conditions define and shape traditional African conceptions, perspectives, beliefs, values, morals, behaviour, attitude, views and practices. [17]

As most of the biblical references to corruption and bribery refer to God’s revelation of his character and the relation between him and his people - as will be indicated later in this article - the main focus in the summary of African Traditional Religion and worldview will now shift towards the traditional African concepts of God.

Traditional African concepts of God and their implications for ethics and stewardship of resources

Although it entails an enormous generalisation to speak of “African Culture and World View” several researchers have pointed out that there are typical aspects of African culture that are generally found on the continent of Africa.

Turaki [18] agrees with many other scholars [19] that five fundamental beliefs, that are found throughout Africa, are the building blocks of African Traditional Religion, philosophy, and worldview. These five fundamental theological beliefs in African traditional religion are beliefs in:

Impersonal (mystical) powers;

Spirit beings;

Divinities/gods;

A Supreme Being; and

A hierarchy of spiritual beings and powers.

Based on his research over many years Van Rooy [20] also indicated how the idea of limited cosmic good is intertwined with the five beliefs listed by Turaki. Cosmic good does not refer to goods in the sense of material possessions, but rather to vital force, power, prestige, influence, health, and good luck.[21]

Although all these fundamental beliefs are related I will now turn to focus on Africa’s belief in a Supreme Being and belief in a hierarchy of spiritual beings and powers.

Supreme Being and a hierarchy of spiritual beings and powers

It is significant that theologians who defended the African "knowledge" of God before the Christian Gospel came to Africa, base their arguments on the African beliefs that God is like a great African chief, who is so "awesome" and unapproachable that petitioners cannot reach Him except through His intermediaries.

The God who is above the lesser gods seems not to be intimately involved or concerned with man’s world. Instead, men seek out lesser powers to meet their desires. This leads people to turn to impersonal powers, divinities, ancestors, and spirit beings for help. God is only occasionally mentioned, remembered, or approached. This belief seems to foster a form of spirituality that does not make for intimacy with God, but with the lesser beings, divinities or ancestors. It weakens the development of a strong Christian spirituality and one’s intimate relationship with God.

Researchers on African ethical codes [22] in general agree that the code of norms is not related to any personal communion with God, and therefore has a strongly legalistic character. “It is not done” and “It is taboo,” is sufficient motivation for declaring an action forbidden. Tradition is sufficient authority. For the same reason, this code of norms is strongly negative, concerned with what is forbidden rather than with positive behaviour.

Spirituality without a strong sense of the presence of God lacks a strong concept of the holiness, righteousness, presence, and intimate care and grace of God. [23]

From this, it follows that the only persons worthy to approach the great chief directly are those nearest to him in rank. In the same way, the beings who can approach God directly are the glorified ancestors or the great deities who are nearest to Him. Church leaders of African-initiated churches (AIC) then also refer to the rituals of sacrifices to deities with the practices of sacrifices prescribed in the Pentateuch and Old Testament. [24]

In his book, God: Ancestor or Creator? Sawyer [25] writes:

...First of all, we must remember that life among Africans is communal and therefore we must accept the notion that their God is thought of in terms of the communal system to which they belong...

In relation to this, we have to bear in mind that, in African communities, there is a clear practice of rule by kings or chiefs, and that these chiefs are not easily approachable and are therefore reached only through intermediaries. For all practical purposes, the chief is distant from ordinary men. Even if the chief is present, a petitioner would request the intermediary to pass his plea to the chief." [26]

Sawyer then suggests that the African's attitude to God is a reflection of his experience of his relationship with his chiefs, influenced in certain respects by his attitude to the ancestral spirits.

Since the cosmic good is limited, Africans believe that the amount of good possessed or controlled by a particular person or people can only be increased at the expense of others. [27]

Power and influence may be legitimately increased by a chief or leader since such persons are regarded as the incorporation of the communal good, the pivotal point of the vital force of the group. This idea is projected onto prestigious church leaders as it often happens with leaders in Prosperity Gospel churches. Africans believe that it is the right of a chief to be wealthy and that the more they sacrifice themselves to enrich the chief or tribal leader, the more they themselves will have a life force.

In general, power is sought for its own sake, not for doing good to anyone else, but only for doing good to oneself. This not only implies that people seek power for themselves, but also that people admire power for its own sake, and are impressed with power more than anything else. People do not admire self-sacrifice or devotion to noble ideals. They tend to regard that as foolishness or suspect people who maintain those principles and follow those ideals of having sinister hidden motives. In an ethic where power has become the highest norm, suffering for what is good and right and noble does not make sense. Moral good as conformation to a universal norm for the common good, or for the sake of obedience to God does not make sense in traditional African thinking.

One of the manifestations in Africa of this obsession with power for its own sake is the many dictatorships, presidents-for-life and perhaps even the many one-party states. There are still many dictatorships in Africa, and African peoples put up with whatever these dictators do with a remarkable degree of long-suffering because the power of these people impresses them.

There is also a belief that in some way they share in the power and prestige of the big chief. Therefore chiefs or people higher up in the hierarchy will seldom be kept accountable for corruption and bribery.

In Africa ethical norms, the rules of conduct, are not regulated according to a supposed divine law, but according to several other principles, such as the striving after power, the balance of cosmic good, and obedience to the ancestors and their traditions.

In his research on poverty in Africa, Van Rooy came to the following conclusion:

I would venture to say that, if all other factors change for the better, and this factor of an unbiblical worldview does not change, Africa will remain chained in poverty. On the other hand, if none of the other factors change, but this one factor does change radically, Africa can become a shining example of freedom from poverty. [28]

God’s self-revelation, corruption and bribery

It is significant that when God introduces himself and his character, He immediately refers to bribery:

… the LORD your God is God of gods and Lord of lords, the great, the mighty, and the awesome God, who is not partial and takes no bribe. He executes justice for the fatherless and the widow, and loves the sojourner, giving him food and clothing.

Deuteronomy 10:17–18

On the one hand his absolute sovereignty, majesty and holiness are introduced: He is “God of gods and Lord of lords, the great God, mighty and awesome”. On the other hand, he has tender care for the fatherless, the widow and the sojourner for their daily needs.

Such a description does not admit to the reality of other gods but simply emphasizes the absolute uniqueness and incomparability of the Lord and his exclusive right to sovereignty over his people (cf. Dt 3:24; 4:35, 39).

As Lord over all, he cannot be enticed or coerced into any kind of partiality through influence peddling (v.17) and, in fact, is the special advocate of defenceless persons who are so often victims of such unscrupulous behaviour (v. 18). [29]

The standard commentary of Keil and Delitszch [30] summarizes as follows:

To set forth emphatically the infinite greatness and might of God, Moses describes Jehovah the God of Israel as the “God of gods,” i.e., the supreme God, the essence of all that is divine, of all divine power and might (cf. Ps. 136:2),—and as the “Lord of lords,” i.e., the supreme, unrestricted Ruler (“the only Potentate,” 1 Tim.6:15), above all powers in heaven and on earth, “a great King above all gods” (Ps. 95:3). Compare Rev. 17:14 and 19:16, where these predicates are transferred to the exalted Son of God, as the Judge and Conqueror of all dominions and powers that are hostile to God. The predicates which follow describe the unfolding of the omnipotence of God in the government of the world, in which Jehovah manifests Himself as the great, mighty, and terrible God (Ps. 89:8), who does not regard the person (cf. Lev. 19:15), or accept presents (cf. Deut. 16:19), like a human judge.

The fear of God and transparency before people as criteria for godly leadership, avoiding corruption and bribery

The words of Exodus 18:23 are clear:

Moreover, look for able men from all the people, men who fear God, who are trustworthy and hate a bribe, and place such men over the people as chiefs of thousands, of hundreds, of fifties, and of tens...

Exodus 18:23

Contrary to the Israelite priesthood or the ancient Near Eastern monarchy, the Israelite judiciary was to be appointed on the basis of honesty and ability rather than occupy an office automatically by reason of being born into a hereditary role. [31]

Moses was to select able men (ִmen of moral strength, 1 Kings 1:52) as judges, men who were God-fearing, sincere, and unselfish (gain-hating). [32]

The primary meaning of the fear of God is veneration and honour, reverence and awe. John Murray wrote in Principles of Conduct, “The fear of God is the soul of godliness.” It is the attitude that elicits from our hearts an adoration and love, reverence and honour, focusing with awe not primarily upon the wrath of God but upon the majesty, holiness, amazing love, forgiveness and transcendent glory. This concept is often given as a key to a holistic godly life, and is clearly not an option:

The fear of the LORD is the beginning of wisdom (Prov 9:10)

Live in the fear of the Lord always (Prov 23:17)

fear Him who is able to destroy both soul and body in hell (Matt 10:28)

in all things obey, fearing the Lord (Col 3:22)

Since you call on a Father who judges each man's work impartially, live your lives as strangers in reverent fear (1 Pet 1:17).

True fear of God is a childlike fear. The Puritan Wilhelmus à Brakel speaks of a filial fear that children have for their parents: “… they cannot bear to hear someone speak a dishonouring word about their parents; it grieves them at their heart and they will defend them with all their might.”

To fear God is a combination of holy respect and glowing love. It is at the same time:

a consciousness of being in the presence of true Greatness and Majesty

a thrilling sense of privilege

an overflow of respect and admiration

and perhaps supremely, a sense that God’s opinion about my life is the only thing that really matters.

To someone who fears God, his fatherly approval means everything, and to lose it is the greatest of all grief. To fear God is to have a heart that is sensitive to both his goodness and his graciousness. It means simultaneously experiencing great awe and deep joy, understanding who God is and what He has done for us.

Child-like fear of God produces integrity

Nehemiah is described as a model of integrity. The governors of his time reigned through bribery and corruption. Nehemiah 5:15 says that the preceding governors placed a heavy burden on the people. Their assistants also lorded it over the people. But out of the fear of God, he did not act like that. Where leaders share this sense of awareness that we live coram Deo, before the face of God, a new honesty will mark their speech and make them stand out in the world.

An antidote for the fear of others

A holy fear is a source of joy (Ps 2:11) and a fountain of life. (Pr 14:27) Therefore it produces boldness and bravery. In times of persecution, the fear of God will dominate the fear of man, and cause God’s children to speak out, although fear of man bids them be silent (Ac 4 18–21). Many Christians are afraid to show that they are followers of Christ. Here is the answer to our lack of courage in witness! In the context of his exhortation in Matthew 10:28 Jesus says: “But if anyone publicly denies me, I will openly deny him before my Father in heaven.” (Mt 10:33) The great reformers in history all acted with undaunted bravery. For example, friend and foe alike said of John Knox that he feared no man because he feared God.

Violation of covenantal identity as God’s people results in being cursed by God

When Moses and the priests assembled the multitude on the brink of their entrance to the promised land, they were reminded that they are the people of the Lord and that it was for this reason that their obedience was so crucial (Dt 27:9–10). In the list of curses that follow the violation of specific covenant stipulations, they are specifically warned about the seriousness of the consequences of bribery:

Cursed be anyone who takes a bribe to shed innocent blood.’ And all the people shall say, ‘Amen.’ (

Deuteronomy 27:25.

Because bribery is such a serious sin before God, Samuel called upon God as his witness that he had absolute transparency and never took bribes and the people affirmed God as a witness. A living and existential relationship with Yahweh is the real antidote against corruption and bribery:

Here I am; testify against me before the LORD and before his anointed. Whose ox have I taken? Or whose donkey have I taken? Or whom have I defrauded? Whom have I oppressed? Or from whose hand have I taken a bribe to blind my eyes with it? Testify against me and I will restore it to you.” They said, “You have not defrauded us or oppressed us or taken anything from any man’s hand.” And he said to them, “The LORD is witness against you, and his anointed is witness this day, that you have not found anything in my hand.” And they said, “He is witness.”

1 Samuel 12:3–5.

In the defence of his righteousness before God, Job (cf. 6:22) also claimed that he never took bribes from anyone.

Only a person “who does not put out his money at interest and does not take a bribe against the innocent, is allowed to “sojourn in God’s tent and dwell on his holy hill “ (Ps 15:1).

In the book of Proverbs bribery is described as wicked:

The wicked accepts a bribe in secret to pervert the ways of justice.

Proverbs 17:23.

Bribery is a phenomenon both acknowledged (Prov 17:8) and warned against (Prov 15:27) in the wisdom tradition, and condemned in the Law (Exod 23:8; Deut 16:19). It is a temptation that can overcome even the wise [33].

The admonitions do not only appear in biblical texts but in many Near Eastern wisdom (particularly Egyptian) texts that those who hold political power should shun all corrupt practices. Still, when people see how pervasive abuse of political power is, it is indeed so common that it is impossible to function in politics without being tainted because bribery also undoes the work of wisdom in that it corrupts the heart [34].

When the prophet Isaiah summons God’s people into a courtroom, so to speak, he begins his message by summoning the heavens and the earth to witness the charges God has against his people [35]. In this context, Isaiah underscores the seriousness of corruption and bribery as a rebellion against God and God is represented as burdened with their crimes. God had been pained and grieved by their crimes; His patience had been put to its utmost trial; and now He would seek relief from this by inflicting due punishment on them [36].

Your princes are rebels and companions of thieves. Everyone loves a bribe and runs after gifts. They do not bring justice to the fatherless, and the widow’s cause does not come to them. Therefore the Lord declares, the LORD of hosts, the Mighty One of Israel: “Ah, I will get relief from my enemies and avenge myself on my foes.

Isaiah 1:23–24. [37]

When Paul paints a whole downward spiral of corrupt Christian leaders he emphasizes the necessity of godliness with contentment because those who desire to be rich fall into temptation, into a snare, into many senseless and harmful desires that plunge people into ruin and destruction. For the love of money is the root of all kinds of evil. It is through this craving that some have wandered away from the faith and pierced themselves with many pangs (1 Ti 6:2–10).

This is part and parcel of Christian servant leadership that is needed to avoid corruption, bribery and bad leadership that exploits and manipulates followers for personal gain.

Conclusions

God reveals himself as the sovereign God. He does not need anything from any creature he has created. Therefore it is impossible for any man or spirit to bribe Him (Dt 10:17). His aseity makes him radically different from traditional African God concepts.

In his aseity, he has his existence in and through himself (a se), rather than being dependent in any way on another for his existence [38].

Reformed theologians quite generally substituted the Latin word aseitas with the word independentia (independence), as to express, not merely that God is independent in His Being, but also that He is independent in everything else: in his virtues, decrees, works, etc. [39] As the self-existent God, He is not only independent in Himself but also causes everything to depend on Him. This self-existence of God finds expression in the name of Yahweh. It is only as the self-existent and independent One that God can give the assurance that He will remain eternally the same in relation to His people.

Berkhof continues to explain the aseitas of God as follows:

"Additional indications of it are found in the assertion in John 5:26, “For as the Father hath life in Himself, even so gave He to the Son also to have life in Himself”; in the declaration that He is independent of all things and that all things exist only through Him, Ps. 94:8 ff.; Isa. 40:18 ff.; Acts 7:25; and in statements implying that He is independent in His thought, Rom. 11:33, 34, and in His will, Dan. 4:35; Rom. 9:19; Eph. 1:5; Rev. 4:11, in His power, Ps. 115:3, and in His counsel, Ps. 33:11.40

Scripture in several places teaches that God does not need any part of creation in order to exist or for any other reason. God is absolutely independent and self-sufficient. Paul proclaims to the men of Athens, “The God who made the world and everything in it, being Lord of heaven and earth, does not live in shrines made by man, nor is he served by human hands, as though he needed anything since he himself gives to all men life and breath and everything” (Acts 17:24–25). In this way, God’s self-revelation is the starting point of Paul’s proclamation of God over any traditional thinking of God.

God asks Job, “Who has given to me, that I should repay him? Whatever is under the whole heaven is mine” (Job 41:11). No one has ever contributed to God anything that did not first come from God who created all things. Similarly, we read God’s word in Psalm 50, “every beast of the forest is mine, the cattle on a thousand hills. I know all the birds of the air, and all that moves in the field is mine. If I were hungry, I would not tell you; for the world and all that is in it is mine” (Ps. 50:10–12)" [41]

Biblical ethics and the fight against widespread corruption and bribery must flow from man being created in the image of God and therefore has to reflect God’s character of holiness and justice.

To really strike the deepest roots of corruption and bribery in Africa, it is of crucial importance to study and proclaim God’s revelation of himself in Africa, over against African traditional concepts of God.

Only when people develop an intimate personal relationship of a childlike fear of God will they have the spiritual and moral strength to fight corruption and bribery.

References

[1] P.L.O. Lumumba, 2013. Corruption in Africa. Keynote speech at the 3rd Anti-Corruption Convention in Kampala, Uganda. Listened on May 15, 2019 from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4cbEuwqKKqE

[2] Ibid.

[3] As quoted by Dwight Vogt. What’s the Big Deal About Corruption? Applied Biblical Worldview. Viewed on June 9, 2019 from h ttps://www.disciplenations.org/article/whats-big-deal-corruption/

[4] Transparency International. PEOPLE AND CORRUPTION: AFRICA SURVEY 2015, Global Corruption Barometer. Acessed on May 15, 2019 from w ww.transparency.org

[5] Yusufu Turaki, The Trinity of sin. (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2012), 74.

[6] h ttps://www.sastatecapture.org.za/

[7] Marianne Merten . “State Capture wipes out third of SA s R4.9 trillion GDP - never mind lost trust, confidence, opportunity.” Daily Maverick. Viewed on May 15, 2019 from https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2019-03-01- s tate-capture-wipes-out-third-of-sas-r4-9-trillion-gdp-never-mind-lost-trust-confidence-opportunity/

[8] Sizwe Orkkonneyoo Banzi, Global corruption survey releases devastation stats of coruption in South Africa. Viewed on June 6, 2019 from h ttp://www.trendsdaily.co.za/trending/global-corruption-survey-releases-devastation-stats-of- c oruption-in-south-africa/

[9] Corruption Watch. Corruption in Uniform: When cops become criminals.Viewed on June 13, 2019 from https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2019-06-13-corruption-watch-bribery-abuse-of-power-lead-reports-of-police-corruption/

[10] Sizwe Orkkonneyoo Banzi. Global corruption survey releases devastation stats of coruption in South Africa. Viewed on June 6, 2019 from http://www.trendsdaily.co.za/trending/global-corruption-survey-releases-devastation-stats-of-coruption-in-south-africa/

[11] J.A. Van Rooy. The Christian gospel as a basis for escape from poverty in Africa. In die Skriflig, 33(2) 1999:235-253; Darrow L. Miller & Stan Guthrie. Discipling the nations. The power of truth to transform cultures. (Seattle WA: YWAM publishing, 1998); B.J. van der Walt. Kultuur, lewensvisie en ontwikkeling. ‘n Ontmaskering van die gode van onderontwikkelde Afrika en die oorontwikkelde Weste. (Potchefstroom: Wetenskaplike bydraes van die PU vir CHO, Reeks F2: No. 76).

[12] Georges, Jayson. The 3D Gospel: Ministry in Guilt, Shame, and Fear Cultures. (Kindle Edition, 2014).

[13] Jayson Georges, The 3D Gospel: Ministry in Guilt, Shame, and Fear Cultures. (Kindle Edition, 2014).

[14] The views of Oginga Odinga, a prominent Kenyan politician deserves more in-depth consideration. He was interviewed by Prof. Oruka, an expert of the sage philosophy or worldview of Africa. (cf. H.O. Oruka, Sage philosophy; indigenous thinkers and modern debate on African Philosophy. (Leiden: Brill, 1990), and H.O. Oruka, Oginga Odinga, his philosophy and beliefs. (Nairobi: Initiatives 1992.) Odinga was regarded as a philosophical sage who raised critical questions about what people usually take for granted. Odinga played an important role in the struggle for the independence of his country. But three decades later, he regarded post-independence as in most cases, wasted years and asked for a second liberation – this time not from white but black domination. According to him independence was given formally but not in reality. The previous colonial powers applied indirect economic rule by winning the cooperation of greedy African leaders. Real freedom, however, required also cultural and economic freedom from the outside world. According to Odinga the first liberation instead brought economic stagnation, mismanagement, inefficiency, a lack of accountability, political dictatorship and more. To him colonialism was like a naked poison being forced into one’s mouth while one is struggling to reject it. Post-independence, on the other hand, is like a poison mixed with your favourite drink like greed. But the aim in both was the same.

[15] Transparency International. Corruption in the world. Tranaparency International’s 2014 Corruptions Perceptions Index. Viewed on June 11, 2019 from h ttp://ewn.co.za/Media/2014/12/03/The-2014-Corruption-Perceptions-Index

[16] Heather Marquette. Whither Morality? ‘Finding God’ in the Fight against Corruption. (International Development Department, School of Government and Society, University of Birmingham, Birmingham: Working Paper 41 – 2010); ibid. Corruption, Religion and Moral Development’ Pre-print chapter submitted for the Handbook of Research on Development and Religion, ed. Matthew Clarke, Cheltenham: Edward Elgar, (January 2013) Viewed on May 15, 2019 from https://www.academia.edu/2643869/Handbook_of_Research_on_Religion_and_Development

[17] In this regard very valuable insights have been gained from Yusufu Turaki’s book: Christianity and African gods. A method in theology. (Scientific Contributions of the Potchefstroom University for Christian Higher Education, Potchefstroom 1999.)

[18] Yusufu Turaki, The Trinity of sin. (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2012)

[19] J.S. Mbiti, African Religions and Philosophy. (Heinemann, London, 1969); J.S. Mbiti, Concepts of God in Africa. (Heinemann, London. 1970); G. M. Setiloane, African Theology. (Johannesburg: Skotaville Publishers. 1986); G. M. Setiloane, The Image of God among the Sotho Tswana. (A. Balkema, Rotterdam. 1976).

[20] J.A. van Rooy, “The Christian gospel as a basis for escape from poverty in Africa.” In die Skriflig, 33(2) 1999:235-253

[21] Ibid. 238.

[22] E. Ilogu, Christianity and Ibo culture. (Leiden : Brill. 1974); J.S. Mbiti, The prayers of African religion. (London ; SPCK. 1975); M.J. Mcveigh, God in Africa. Conceptions of God in African traditional religion and Christianity. (Cape Cod : Claude Stark. 1974); E.I. Metuh, God and man in African religion. (London : Geoffrey Chapman. 1981); G.M. Setiloane, The image of God among the Sotho-Tswana. (Rotterdam : Balkema. 1976).

[23] Turaki, 2012:25

[24] In a Masters degree level research project Pastor Nicolas Nyawuza has revealed through empirical research how many pastors of AIC churches use Numbers 19 to include typical traditional African cleansing rituals (called hlambulula in the isiZulu language) in their Christian worship services. Cf. Nicolas Nyawuza. Purification in an African context from a missio-Dei perspective: Empowering pastors of African Independent Churches at Leandra to interpret the cleansing rituals of Numbers 19 from a Christ-centred redemptive perspective, a case study. Dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree Magister Artium in Missiology at the Potchefstroom Campus of the North-West University 2013.)

[25] As quoted by Leonard Nyirongo. THE GODS OF AFRICA OR THE GODS OF THE BIBLE? The snares of African traditional religion in Biblical perspective. (Potchefstroom: Scientific Contributions of the Potchefstroom University for Christian Higher Education. Series F2: Brochures of the Institute for Reformational Studies No. 70. 1997), 16

26 ibid.

[27] Van Rooy, “The Christian gospel as a basis for escape from poverty in Africa.” In die Skriflig, 33(2) 1999:235-253.)

[28] Ibid.

[29] E. H. Merrill, Deuteronomy (Vol. 4, Nashville: Broadman & Holman Publishers. 1994) 203–204.

[30] C. F. Keil, & F. Delitzsch, Commentary on the Old Testament Vol. 1, (Peabody, MA: Hendrickson 1996). 899.

[31] D. K. Stuart, Exodus (Vol. 2). (Nashville: Broadman & Holman Publishers. 2006). 418.

[32] C. F. Keil, & F. Delitzsch. Commentary on the Old Testament Vol. 1. (Peabody, MA: Hendrickson. 1996), 377.

[33] R. Murphy, Ecclesiastes Vol. 23A, (Dallas: Word, Incorporated, 1992), 64.

[34] D. A. Garrett, Proverbs, Ecclesiastes, Song of songs, Vol. 14, (Nashville: Broadman & Holman Publishers, 1993), 320.

[35] T. R. Briley, Isaiah. (Joplin, MO: College Press Pub. 2000–), 39.

[36] J. P Lange, P Schaff,C. W. E., Nägelsbach, S. T. Lowrie, & D. A. Moore. Commentary on the Holy Scriptures: Isaiah (Bellingham, WA: Logos Bible Software. 2008), 49.

[37] Cf. also Isaiah 5:23; 33:15; Amos 5:12; Micah 3:11-12; 7:3 to see how the prophets declare the anger of God over the corruption and bribery of leaders in Judah and Israel.

[38] W. G. T. Shedd, Dogmatic theology. (A. W. Gomes, Ed.) (3rd ed.), Phillipsburg, NJ: P & R Pub. 2003), 952;

[39] L. Berkhof, Systematic theology. (Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans publishing co. 1938), 58.

40] Ibid.

[41] W. Grudem, Independence of God. Viewed on June 13, 2019 from h ttps://www.monergism.com/independence-god

Discussion